One of the difficulties when reporting statistics concerning Russia or the European Union in these chaotic times is the ultra-partisan nature of contemporary thought. Anything pro-Russian or Western-negative is automatically regarded as suspect and not to be trusted. Such items are also avoided as subjects for discussion in Western media. Hiding the truth has always been a politicians’ standard tool for denying bad news (or blaming it on others) while seeking to distract attention away from inconvenient realities.

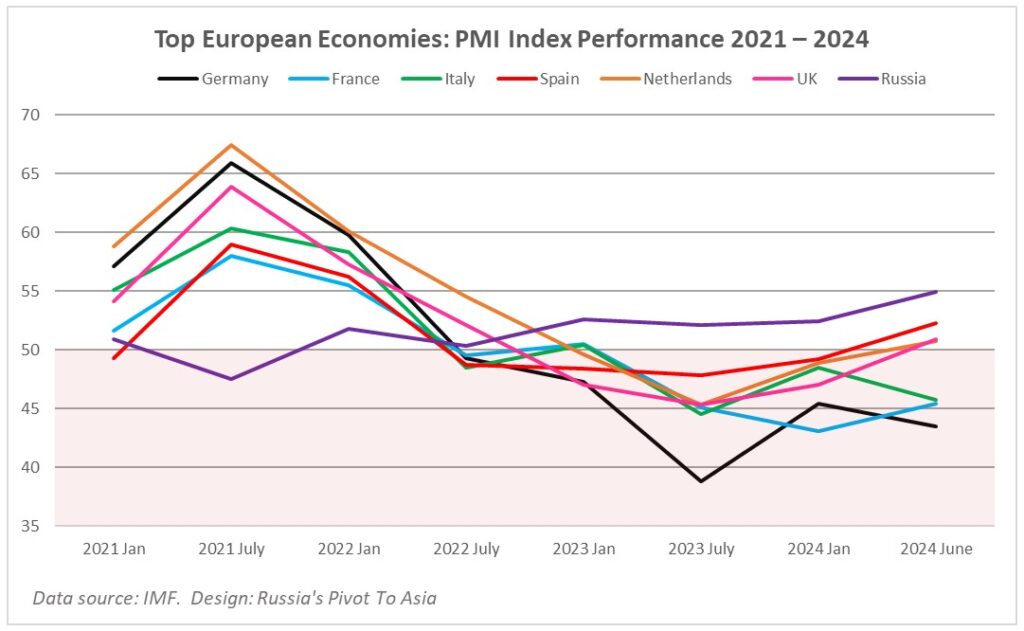

Research into subjects which may carry negativity is also discouraged. This then expands problems that would otherwise be politically recognised and delays the ability to correct them. To provide some economic perspective, Russia’s Pivot To Asia has conducted analysis on two fundamental aspects of the recent fiscal behaviour of the European Union, and Russia. These are the Purchasing Manufacturers Index (PMI), which is used to assess the state of economic buoyancy in specific economies. They assess orders from Purchasing Managers across a wide variety of industries, and thus ascertain consumer market sentiment. Any number above a base line of 50 is growth; below is a manufacturing retraction. If numbers remain below 50 for three consecutive months, such economies are technically considered in recession.

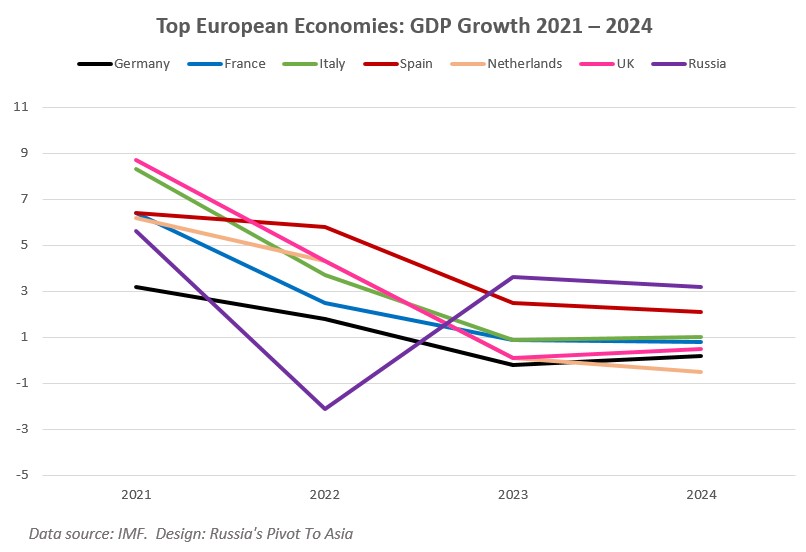

The second measurement is GDP growth. This measures whether economies have expanded or contracted.

In this study we have included the top five European Union economies, who account for the bulk of the total EU economic performance, being Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands. We have also included the United Kingdom, a major European economy in its own right. Finally, we compare this with Russia’s performance.

We have examined data issued by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), part of the World Bank – meaning our observations can hardly be considered biased. What we have done is illustrate this data in graph form to enable readers to easily view the relative performances. The results make interesting reading.

A number of observations can be made from these findings. First, that the European economies experienced an immediate manufacturing confidence boom in 2021. They had all been doing well in the post-covid recovery period, with consumer expectations in the mid-high 50’s, all positive figures. Even the somewhat sluggish Russian economy was growing, albeit at a slower rate. This then markedly changed from the date of the initial concerns in mid-2021 that Russia could be prepared to invade Ukraine. That implies that the EU anticipated such an event could, or would occur, with the manufacturing boom going towards increased military supplies. This coincided with a lack of confidence in the Russian economy as conflict appeared increasingly likely. One can read further political analysis into this, suggesting that the EU originally thought that such a conflict would be positive for their own economies, and create negative consequences for Russia.

That initial boost helped create a political bonus that Western politicians were quick to act on, threatening sanctions and suggesting that the Russian economy would be destroyed. Much of that political rhetoric remains, however is merely now an echo of economic performances now three years distant. However, this political dogma has now become detached during this period from the actual economic reality.

What happened once conflict broke out is that all the EU economies, plus the UK and Russia, experienced an immediate downturn. War has the immediate impact of creating consumer concerns, and that is adequately illustrated in this graph. Sanctions were placed on Russia from February 2022 with an immediate impact. All the European economies dropped below the 50 percent growth benchmark, representing an absolute contraction by mid-2022.

Russia however had begun to put into place fiscal measures to counteract against the sanctions’ measures, and their economy began to rebound and move into manufacturing growth at this same time. This suggests that Russia had prepared itself for Western sanctions and that measures were then being taken to mitigate against them – a large part of which was changing its supply chains to Asia and the Global South. As can be seen, the negative period of Russia’s manufacturing performance lasted for a 12-month period during 2021, and apart from a further drop – but not into negativity – in mid-2022, has continued to grow. In total, the manufacturing decline in Russia created by Western sanctions lasted just one year and was overturned by early 2022.

This contrasts with the impact upon the European economies. All continued their decline for an additional twelve months, lasting until mid-2023. There has been slow recovery, but all, except for Spain, remain either at negative, or at best minimal growth. The German and Italian economies remain in deep trouble. Russia’s PMI growth figures are now the highest of all.

This implies that Russia did its fiscal homework and had war-gamed the economic impact of sanctions, whereas European politicians did not. This further brings into question the fundamental misunderstandings that Europe has as regards the Russian economy and begs the question of what were EU economists involved in Russia doing in the period to 2022? This further suggests that European political rhetoric concerning Russia had already replaced fiscal analytical fundamentals in terms of research, or that any research conducted was later contaminated by political dogma.

Russia’s PMI decline lasted 12 months. Europe’s has lasted for three years and shows little sign of significant recovery.

The GDP graph also closely follows the PMI predictions. However, there is one change in that the European economies, which had been growing at rates between 3 and close to 9 percent at the beginning of 2021, all began to slip in GDP growth almost immediately. Russia was the worst affected during the course of that year, slipping from growth of nearly 5% to -2.5% in twelve months. Again, that fit into the same timeframe as Western politicians predicting the complete demise of the Russian economy and which some continue to expound.

But from 2022 things began to change – Russia’s GDP began to grow again and by the end of 2023 had overtaken all the other major European economies. IMF forecasts indicate that it is expected to slow slightly to about 3.2% by the end of this year, however, is still performing rather better than Europe. Spain is doing best at 2% while all other European economies are relatively moribund at between zero and 1% growth. None, with the possible exception of Russia, appear set to turn their economies back towards pre-conflict growth anytime soon. How well Russia does, depends upon its ability to continue anti-sanctions measures – an issue that to date, it has shown significant capabilities in implementing. It should be remembered that Russia has attained this growth despite the extraordinary attempts to hamper exactly this.

The caveat here for the European economies is how far they are prepared to continue to go down this path. In fiscal and economic terms, the past four years have been a disaster. Russia’s economic downturn lasted one year; Europe is now well into its third.

For Europe, there are more worrying signs. Taxes are on the increase throughout many European economies, indicating that European citizens and its businesses are now expected to pay more for their politicians’ policies. That also becomes, curiously enough, a democratic issue: thus far, no mandate on spending European money on supporting either Ukraine, or the conflict with Russia has yet been held.

From purely the fiscal perspective, the damage wrought upon Europe’s economies has both been significant and ineffective. The blame for that must lie, at least partially, at the door of the European politicians. Europe failed to understand Russia’s economic strengths and the economic repercussions of the sanctions policies it follows. In the corporate world, CEOs and CFOs would be fired for such performances.

Politicians however can point to a ‘mandate’ from the people. This now appears to be a form of democratic fait accompli – it is difficult to gauge a European mandate to end this conflict when no European politicians – with the sole exceptions of Hungary’s Victor Orban and Slovakia’s Robert Fico – have shown any indication that they are willing to do so. Does this truly represent power for the people? Or vested interests consolidated elsewhere?

Europeans should be extremely concerned. Their fiscal and economic future looks anything but secure. While concentrating on inflicting damage to the Russian economy, European politicians have neglected their own. Russia, meanwhile, while the target of fiscal punishments, is adapting. Neither scenario was in the original Western script.

Further Reading

Russia’s Pivot To Asia 2024 is a comprehensive PDF guide that details Russia’s emerging trade and investment dynamics throughout Asia and the Global South. It is a complimentary download and may be accessed in English here and Russian here.

Русский

Русский