By design, South Asia should be one of the world’s most integrated economic regions. In reality, it remains one of the least connected. South Asia is not a marginal periphery of Eurasia as one of its demographics, economic, and logistical cores. Yet its regional institutions remain weaker than its potential. For Russia, this contradiction is not an obstacle but a strategic opening – if the component parts are properly understood and acted upon.

South Asia’s Strategic Weight in the 21st Century

South Asia represents one of the most paradoxical regions in the global political economy. Home to nearly 2.4 billion people, accounting for almost one quarter of humanity, the region collectively produces more than US$25 trillionin purchasing power parity terms. It hosts some of the world’s fastest-growing economies, emerging industrial hubs, critical sea lanes, and continental transit routes linking Eurasia, the Middle East, and the Indo-Pacific. Yet despite these structural advantages, South Asia remains one of the least economically integrated regions in the world. Intra-regional trade constitutes only 5-6 percent of total South Asian trade, compared with over 35 percent in East Asia and nearly 60 percent in the European Union. The gap between potential and reality is not economic but it is political.

South Asia’s Population & Economy (GDP PPP) In Numbers

| SN | Country | GDP (PPP) USD, 2025 | Bilateral trade with Russia, 2024 | Population | Population projection 2040 |

| 1. | India | $21.848 trillion | $68.7 billion | 1.46 billion | 1.67 billion |

| 2. | Pakistan | $2.058 trillion | Over $1 billion | 257 million | 371 million |

| 3. | Bangladesh | $2.1 trillion | Over $2 billion | 175 million | 214 million |

| 4. | Afghanistan | $183 billion | $1 billion | 44 million | 76.8 million |

| 5. | Sri Lanka | $422 billion | @ $700 million | 23 million | 24.8 million |

| 6. | Maldives | $15 billion | $1.12 million | 530,540 | 589,962 |

| 7. | Nepal | $253.92 billion | $21 million | 29.6 million | 34.6 million |

| 8. | Bhutan | $20.47 billion | @ $28,000–30,000 of exports to Russia but no imports | 799,046 | 882,340 |

| 9. | Total | $25 trillion | $73.42 billion | @ 2 billion | 2.39 billion |

At the institutional level, this contradiction is embodied in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). Established in 1985 with the ambition of encouraging collective prosperity, SAARC today is largely immobilized, unable to convene regular summits or implement meaningful economic integration.

For Russia, a power historically engaged in South Asia through bilateral diplomacy, energy cooperation, defense partnerships, and political balancing, the region’s institutional paralysis raises a fundamental question: how can Moscow integrate into South Asia’s future growth while navigating its fractured regional architecture?

SAARC: Institutional Potential and Structural Stagnation

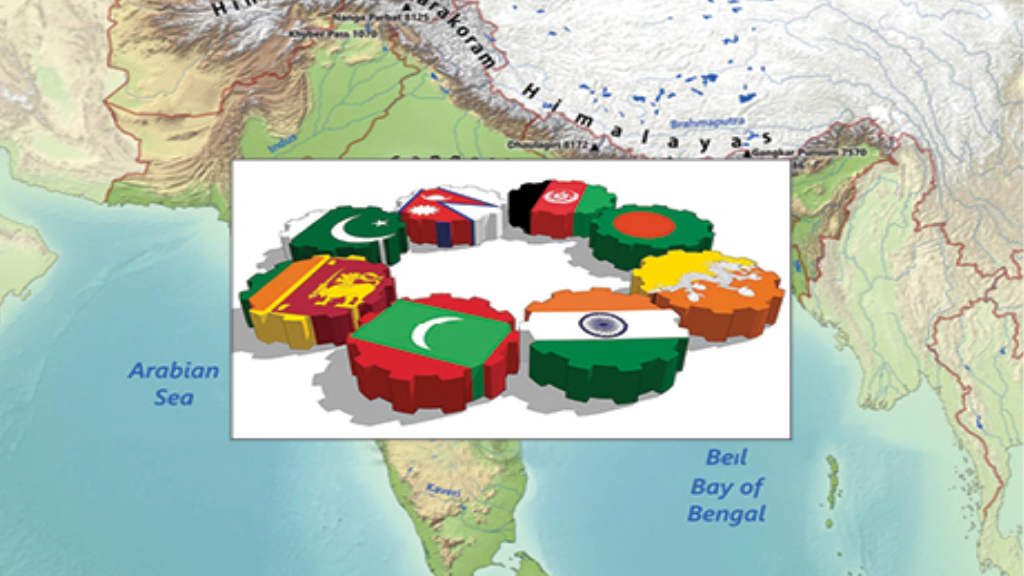

SAARC comprises eight member states: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives, and Afghanistan (currently inactive and non-functional due to South Asian complex geopolitics over India- Pakistan rivalry). In theory, SAARC offers Russia a single multilateral gateway into South Asia’s economy. From an institutional perspective, SAARC was conceived as a single multilateral framework capable of promoting economic integration and regional stability in one of the world’s most dynamic regions. In practice, it remains an under-performing mechanism constrained by structural weaknesses, internal contradictions, unresolved political disputes and complex geopolitical realities. Despite significant demographic and economic potential, SAARC has failed to evolve into an effective mechanism of regional cooperation. Its limited functionality has reduced its relevance both for member states and for external partners, including Russia.

Economic Capacity and the Gap Between Potential and Reality

Collectively, SAARC member states account for more than US$900 billion in annual global trade. The region is characterized by rapid population growth, expanding middle classes, and rising demand for energy resources, fertilizers, infrastructure development, and modern technologies. Nevertheless, intra-SAARC trade remains below US$50 billion per year and has shown little progress over the past decade.

This persistent stagnation is primarily explained by structural factors: high tariff and non-tariff barriers, extensive sensitive lists excluding key goods, weak cross-border transport infrastructure, limited financial integration, and, above all, political mistrust among major regional actors. UNESCAP and SAARC studies have long warned that South Asia’s economic fragmentation is artificial, not structural: with genuine integration, streamlined trade facilitation, and the removal of entrenched barriers, intra-SAARC trade could rapidly double or even triple, surpassing US$170 billion, more than five times current volumes. Realizing this latent potential demands not rhetoric, but hard investment in connectivity, cross-border infrastructure, harmonized regulations, and sustained coordination between businesses and policymakers.

In this context, Russia’s vision for the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) offers a natural Eurasian bridge, linking South Asia to Russian and EAEU markets through reliable, cost-efficient routes. High-quality Russian products such as energy, fertilizers, machinery, grain, and industrial technologies are not merely competitive but structurally suited to South Asia’s development needs, positioning Moscow as a pragmatic partner in transforming unrealized regional potential into tangible economic reality.

South Asia today represents a near-US$25 trillion economy in PPP terms and a consumer market approaching 2.4 billion people, yet Russia’s total trade with the entire region remains just US$73.4 billion, overwhelmingly concentrated in India. While Russia–India trade has grown rapidly, it is still far below the region’s real absorption capacity, and Russia’s economic engagement with Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Afghanistan remains modest at barely US$4 billion in trade, despite a combined consumer market of approximately 476 million people. It is also structurally underutilized, given their combined US$6 trillion-plus PPP economies and fast-expanding consumer bases.

Even more striking is the near absence of Russian trade with Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, and Maldives, economies where Russian food, energy, fertilizers, machinery, tourism services, and industrial inputs are naturally competitive. This imbalance is not a market failure but a connectivity and policy gap, reflecting weak logistics, limited trade finance, and the absence of region-wide economic frameworks.

Figures such as US$700 million in Sri Lanka–Russia trade, US$21 million with Nepal, US$1.12 million with the Maldives, and a tiny US$28,000 in Bhutanese exports with no reciprocal imports from Russia in 2024 – despite a combined consumer market of nearly 70 million people – do not reflect market realities, but rather a clear absence of strategic focus.

For Russian analysts, these numbers highlight how entire South Asian economies remain effectively off the radar of Russia’s trade policy, despite evident demand for Russian energy, food, fertilizers, and industrial goods. At the comprehensive economic partnership level in economic diplomacy, this is not a failure of competitiveness, but a failure of prioritization, connectivity, trade and institutional engagement.

Prioritizing trade pragmatism over neglect in these 4 countries alone could raise Russia’s trade volume by at least US$5 billion in the near term. With improved connectivity, particularly through the International North-South Transport Corridor, and targeted sectoral engagement, Russia’s trade with South Asia could realistically exceed US$150 billion in the medium term. For Moscow, the strategic choice is clear: remain a neutral peace mediator working to narrow divisions among South Asian nations; enhance its role through alternative regional trade alignments; and emerge as a systemic Eurasian economic stakeholder shaping South Asia’s long-term growth trajectory.

SAPTA and SAFTA: Institutional Mechanisms Without Economic Impact

The SAARC Preferential Trading Arrangement (SAPTA), introduced in the 1990s, sought to encourage gradual tariff reductions. However, its limited scope and lack of enforcement mechanisms rendered it ineffective. The South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA), operational since 2006, aimed to reduce tariffs to 0-5 percent across the region. In reality, sensitive lists remain extensive, key sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing are protected, and trade normalization between India and Pakistan has not occurred. As a result, SAFTA remains largely declarative, reinforcing perceptions of SAARC’s limited economic credibility. If the two trade frameworks, SAPTA and SAFTA, were fully effective and integrated with the EAEU, Eurasian economic integration could reach unprecedented levels, with trade values likely exceeding US$500 billion.

India-Pakistan Rivalry as a Structural Constraint

The primary factor behind SAARC’s stagnation is the enduring rivalry between India and Pakistan. This confrontation is not episodic but structural, shaping regional politics and institutional paralysis. India accounts for more than 80 percent of SAARC’s total GDP and industrial capacity. Pakistan, meanwhile, controls key overland routes connecting South Asia with Central Asia and the Middle East.

Although the potential volume of bilateral trade between the two countries is estimated at US$37 billion annually, actual official trade remained below US$1 billion billion in 2025 and is frequently disrupted by political crises. Each escalation leads to the suspension of SAARC summits, cancellation of ministerial meetings, and freezing of regional initiatives. The estimated US$10 billion in informal India-Pakistan trade demonstrates the immense potential of cross-border commerce—not only for both countries themselves but also for Russia, if normal economic activities resume and SAARC is effectively revitalized. Smaller South Asian states have increasingly responded by lowering expectations from SAARC and seeking alternative regional and bilateral formats. For Russia, however, this rivalry also creates diplomatic space. Moscow maintains stable working relations with both New Delhi and Islamabad and is not perceived as an ideological or interventionist actor in the region.

SAARC’s Residual Relevance for Russia

Despite its limited effectiveness, SAARC retains a degree of strategic significance. It provides a multilateral framework beyond bilateral diplomacy, offers institutional legitimacy for engagement in South Asia, and corresponds with Russia’s broader Eurasian integration agenda. Even partial revitalization through technical, non-political cooperation particularly in energy, food security, digital infrastructure, and transport connectivity could produce tangible benefits.

Bangladesh’s Strategic Pivot: A Window of Opportunity for Russia in South Asia

The August 2024 political transitions in Bangladesh signal a potential new vitality in South Asian trade dynamics. Following the regime shift on 5 August, Dhaka has sought to revitalize SAARC and normalize ties with Pakistan, yet the entrenched India factor has constrained these efforts. Undeterred, Bangladesh has continued to strengthen its role in BIMSTEC, positioning itself as the critical bridge linking South and Southeast Asia. The BIMSTEC chairmanship was officially handed over to Bangladesh. Its geostrategic leverage, combined with a proactive trade agenda, marks Bangladesh as an extraordinary regional actor. Simultaneously, Dhaka has been pursuing a newtrade alignmentwith Pakistan, Afghanistan,and China, seeking to establish a fresh South Asian trade block.

Notably, Pakistan and Afghanistan remain outside BIMSTEC, making this emerging China-Bangladesh-Afghanistan-Pakistan axis a strategic complement rather than competitor to the existing regional architecture. For Russia, this dual-track evolution offers unprecedented economic opportunities. Through BIMSTEC, led by India, Moscow can engage a mature, structured trade framework, while the China-Bangladesh-Afghanistan-Pakistan alignment provides access to untapped markets and high-growth corridors.

Russia’s position here is uniquely advantageous: it maintains strong bilateral relations with both India and China, while being the only major power to officially recognize the Taliban-led government in Afghanistan. This recognition opens the door to trade with Afghanistan at an extraordinary scale, including energy, machinery, and industrial goods, creating a corridor that few other nations can exploit.

Strategically, Moscow must balance its diplomatic engagement across these two axes, leveraging Bangladesh’s pivotal role in South and Southeast Asian and ASEAN-BIMSTEC trade connectivity to expand its economic footprint while mitigating regional friction. In this context, Russia’s path is clear: it must act as a pragmatic facilitator, a trade bridge, and a reliable partner across both emerging regional blocks. By doing so, Moscow can transform South Asia’s latent market potential encompassing hundreds of millions of consumers into tangible economic gains, reinforcing its Eurasian integration strategy and asserting its role as a central player in the evolving Asian economic order.

BIMSTEC: A More Functional Regional Format

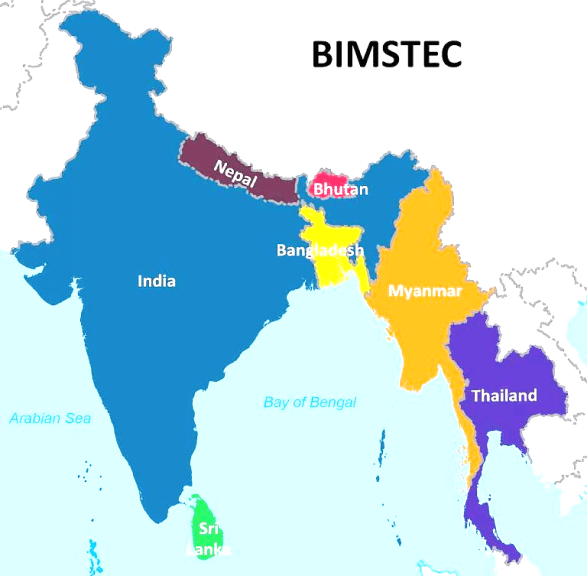

Against the backdrop of SAARC’s stagnation, the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) has emerged as a more pragmatic platform. Its membership excludes Pakistan and Afghanistan, allowing it to avoid the principal political blockage affecting SAARC. BIMSTEC’s maritime orientation, strong links with ASEAN, faster decision-making mechanisms, and focus on trade facilitation and energy cooperation enhance its practical relevance. BIMSTEC, uniting Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Thailand, stands as South Asia’s most functional economic framework, bypassing India–Pakistan tensions and offering Russia a reliable platform for trade and investment. Connecting over 1.82 billion consumers across diverse markets, it spans energy, machinery, industrial goods, and strategic logistics corridors. With a GDP (PPP) of 27.44 trillion, BIMSTEC is poised to become a key and effective regional bloc in South and Southeast Asia.

For Moscow, deep engagement with BIMSTEC is not just commerce but a strategic opportunity to cement Russia’s role as a central Eurasian economic power and a bridge between South and Southeast Asia. Russia’s trade with BIMSTEC countries already exceeds its trade with SAARC as a bloc, driven primarily by India, Thailand, and Bangladesh. For Russia, BIMSTEC aligns with Indo-Pacific logistics, maritime energy security, Russia-ASEAN cooperation, and the eastern vector of foreign policy.

Nearly two decades after the signing of its framework agreement in 2004, the BIMSTEC Free Trade Area remains stalled, reflecting the bloc’s broader institutional inertia. Despite ambitious plans linking trade, connectivity, and investment, implementation has lagged behind rhetoric. However, BIMSTEC member states have continuously stated their commitment and willingness to discuss and implement the Free Trade Area plan. As BIMSTEC struggles to convert potential into outcomes, member states are increasingly exploring alternative economic pathways.

India is moving toward an FTA with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), while Thailand has initiated similar negotiations. Myanmar has expressed interest in EAEU membership, and Bangladesh has proposed an FTA with the bloc. These shifts underscore a growing perception that Eurasian-led integration may deliver what BIMSTEC has yet to achieve.

The 6th BIMSTEC Summit, held in Bangkok on 4 April 2025 under the theme “PRO BIMSTEC: Prosperous, Resilient and Open BIMSTEC,” marked a significant step forward with the adoption of the Bangkok Vision 2030, the Maritime Transport Pact and Signing of the Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) between BIMSTEC and Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA).

These developments present a timely opportunity to align Russia’s Pivot to Asia strategy with BIMSTEC’s evolving vision, particularly through synergies with the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) and the Chennai-Vladivostok maritime corridor. Thailand’s Ranong Port could be strategically connected with India’s Mumbai and Chennai ports, extending onward to Iran’s Chabahar and other Iranian ports via Bangladesh’s Chittagong, Myanmar’s Yangon and Sittwe, and Sri Lanka’s Colombo and Hambantota. Landlocked Nepal and Bhutan could also be integrated into this network through Indian ports such as Kolkata and Haldia, as well as Bangladesh’s Chittagong.

Such a framework would significantly enhance BIMSTEC maritime connectivity while facilitating the broader integration of Eurasia with the Indian Ocean, Bay of Bengal region, Arabian Sea and Asia Pacific. In parallel, linking these routes to Russia’s Far Eastern and Arctic corridors via Chennai and Vladivostok would anchor BIMSTEC within a wider Eurasian logistics architecture, reinforcing multipolar connectivity across continents.

BIMSTEC Population & Economy (GDP PPP) In Numbers

| SL | Country | GDP (PPP) | Bilateral trade with Russia | Population | Population projection |

| 01 | India | $21.848 trillion | $68.7 billion | 1.46 billion | 1.67 billion |

| 02 | Myanmar | 495 billion | $2 billion | 55 million | 58 million |

| 03 | Thailand | 2.28 trillion | $1.58 billion | 71.6 million | 66.3 million |

| 04 | Bangladesh | $2.1 trillion | Over $2 billion | 175 million | 214 million |

| 05 | Sri Lanka | $422 billion | @ $700 million | 23 miilion | 24.8 million |

| 06 | Nepal | $253.92 billion | $21 million | 29.6 million | 34.6 million |

| 07 | Bhutan | $20.47 billion | @ US$28,000–30,000 of exports to Russia but no imports | 799,046 | 882,340 |

| 09 | Total | $27.44 trillion | @ $74 billion | 1.82 billion people | 2.07 billion people |

Country Specific Opportunities

India

India remains Russia’s principal partner in South Asia. Bilateral trade has exceeded USD 65 billion, supported by cooperation in energy, nuclear power, defense, pharmaceuticals, and information technologies, as well as logistics development through the INSTC. At the same time, India’s limited engagement with SAARC constrains the organization’s regional role. Russia–India trade and investment potential remains strong, supported by energy, defense, fertilizers, and connectivity projects.

Within a BIMSTEC-focused regional outlook, India acts as a gateway to Bay of Bengal markets, while Russia provides capital, technology, and resources, enhancing multipolar economic integration and South–South cooperation. India’s recent identification of 300 exportable products and resilient Russian crude imports exceeding one million barrels per day despite Trump pressures, signal deepening Russia–India economic cooperation. Despite sanctions pressure, trade momentum supports the US$100 billion target and, within a BIMSTEC framework, can catalyze wider regional integration and supply-chain collaboration. By 2050, India’s 1.67 billion-strong consumer market will be a key destination for Russian oil and non-oil products, offering vast opportunities in energy, fertilizers, defense equipment, and industrial goods. Expanding trade ties within BIMSTEC can further strengthen regional supply chains and economic integration.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh is one of the fastest-growing economies in South Asia, with expanding manufacturing capacity and rising import demand. Russian participation in the Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant illustrates the long-term nature of bilateral cooperation. Russia–Bangladesh trade has crossed US$2 billion, with Russian investment around US$12.65 billion, led by nuclear energy and infrastructure. Bangladesh needs fertilizers and wheat, which Russia can supply, while Dhaka’s apparel exports are rising in Russia. Within BIMSTEC, labor cooperation and skills mobility can offset Russia’s shortages and support Bangladesh’s growing population. With a population projected at 214 million by 2050, human resource development cooperation can address Russian labor shortages through skilled Bangladeshi migration.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s strategic location in the Indian Ocean enhances its importance as a maritime and logistics hub. Russian engagement supports broader regional transport and energy transit objectives. Russia–Sri Lanka trade and investment potential is growing, with bilateral trade modest (around US$700 million) but strategic, focused on tea, apparel, tourism, and energy. Russian investments target ports, renewable energy, and infrastructure.

Within BIMSTEC, enhanced connectivity and joint projects can boost regional integration, diversify Sri Lanka’s economy, and expand Russia’s influence in South Asia. Within bilateral and BIMSTEC frameworks, Russia–Sri Lanka trade could realistically grow to US$2.5 billion by 2030, driven by energy, tourism, tea, apparel, and infrastructure investments. Enhanced connectivity, joint projects, and regional supply-chain integration will strengthen economic ties and create new opportunities for both nations within South Asia. Russia sent 34 tons of humanitarian aid to Sri Lanka, demonstrating solidarity amid devastating floods that have disrupted food security.

Russian agro-based companies can efficiently supply essential food and agricultural products, helping Sri Lanka meet urgent needs. Within BIMSTEC and bilateral frameworks, this strengthens trade, humanitarian cooperation, and regional resilience. The 30-year lease of Hambantota Airport to India’s Shaurya Aeronautics and Russia’s Airports of Regions positions Russia to gain strategically and economically. Russian expertise in airport management enhances regional presence, opens opportunities in logistics, aviation services, and tourism, and strengthens BIMSTEC-linked connectivity, reinforcing Moscow’s influence in South Asia.

Thailand

Russia-Thailand trade reached US$1.8 billion in 2024, with Russian investments surpassing US$6-7 billion, dominating 40% of Thai real estate. Fertilizer exports rose 50%, while Thai rubber imports into Russia grew 28%, signaling growing economic complementarity. Tourist flows from Russia are projected to reach 2 million for 2025, boosting HoReCa and retail sectors. Bilateral cooperation in digitalization, biotech, AI, and renewable energy promises to unlock Southeast Asia’s strategic economic potential. Thailand’s GDP is projected to reach US$2.5 trillion by 2030, creating vast investment opportunities spanning digital, energy, biotech, and infrastructure. Bilateral cooperation underpins Eurasian-BIMSTEC-ASEAN integration, strengthening Russia’s strategic footprint in Southeast Asia.

Myanmar

Russia-Myanmar trade reached nearly US$2 billion in 2024 and can be expanded to US$4 billion by 2030, driven by energy, agriculture, nuclear energy and military-industrial and hi-end manufacturing cooperation. Russia supplies significant portion of Myanmar’s crude oil, while fertilizer exports support agricultural modernization.

Joint projects include a natural fertilizer plant, Dawei SEZ, oil refinery, and 110 MW nuclear plant, signaling industrial and energy integration. Direct flights, mutual visa-free travel, and digital payment systems strengthen connectivity and trade facilitation. Russian investment in infrastructure, technology, and human capital positions Myanmar as a gateway to Southeast Asia and a hub for Eurasian-Indo-Pacific economic corridors. The partnership exemplifies complementary strengths, strategic foresight, and resilient bilateral growth amid global economic challenges.

Nepal and Bhutan

Nepal and Bhutan, while small in economic scale, offer niche opportunities in hydropower, tourism, climate resilience, and disaster management cooperation. Russia’s trade, economic, and investment engagement with them remains selective but strategic. The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), combined with Bangladesh and India’s connectivity, can help Nepal and Bhutan overcome landlocked constraints, providing direct access to global and Eurasian markets. This corridor strengthens regional trade, reduces transit costs, and enhances BIMSTEC integration, positioning Russia as a key partner in South Asia’s economic connectivity.

Trade with Nepal and Bhutan remains significantly underutilized and presents significant opportunities. Russian companies and investors, for example from Russia’s similarly Buddhist Kalmykia Republic could target these growing markets – Nepal’s population is projected to reach 34.6 million and Bhutan’s at 882,340 by 2050. Expanding exports, technology, and infrastructure investment can unlock regional integration and strengthen Russia’s economic footprint in South Asia. Similar Buddhist related commercial ties could also be made with Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Thailand.

Nepal

Current bilateral trade is less than US$30 million; Russia supplies fertilizers, energy equipment, and technical expertise. Potential exists in hydropower and infrastructure development. Nepal is investing in human resource development, creating opportunities for skilled labor growth. Russia can cooperate by facilitating training, technology transfer, and labor mobility, helping address domestic labor shortages while providing Nepalese professionals access to Russian industries, strengthening bilateral ties and regional workforce integration within BIMSTEC frameworks.

Bhutan

Trade is underutilized at less than US$20 million, and focuses on hydropower, energy, and tourism services. Russian investment can support Bhutan’s renewable energy ambitions. Within BIMSTEC, Russia can strengthen regional integration, leverage infrastructure and energy projects, and promote labor and skill cooperation to complement local development needs. Bhutan, being landlocked, relies on neighbors for trade transit. Russia has offered cooperation in supplying equipment, technology, and natural resources, enabling Bhutan to diversify imports, strengthen infrastructure, and support sustainable development. Within BIMSTEC and bilateral frameworks, this partnership enhances regional connectivity and reinforces Russia’s strategic economic presence in South Asia.

Emerging Informal Regional Alignments

In parallel, an informal alignment involving China, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan is developing around infrastructure, logistics, and manufacturing projects. This model reflects a shift toward project-based regionalism rather than institutional integration. Sri Lanka and the Maldives could also join. Afghanistan and the Maldives have given in-principal approval to become members of the organization. For Russia, pragmatic engagement without ideological alignment is essential in areas such as infrastructure development, energy exports, food security supply chains, and multi-modal transport corridors. Since 2019, China has maintained a Free Trade Agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), while Pakistan and Russia are actively pursuing to sign the similar arrangement. Islamabad has also signaled its intention to join the EAEU, and Bangladesh’s interest in concluding an FTA with the bloc is accelerating.

Collectively, these developments point toward the gradual emergence of a wider free trade space linking South Asia with Eurasia. At the same time, connectivity potential through the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) remains substantial. China’s landlocked western regions could access the INSTC via the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, reaching Gwadar Port and onward to Iran. Bangladesh’s recent resumption of Chittagong–Karachi maritime connectivity, alongside proposed links between Chittagong, Karachi, and Gwadar, complements Sri Lanka’s Colombo hub and enables the integration of landlocked Afghanistan through Pakistani and Iranian ports. Together, these corridors would form a resilient and stable supply-chain network connecting the Greater Eurasian partnership with Russia at its core.

The Pakistan-Bangladesh-China-Afghanistan Axis: Population & Economy (GDP PPP) In Numbers

| SL | Country | GDP (PPP) | Bilateral trade with Russia in 2024 | Population, 2025 | Population projection by 2050 |

| 01 | China | $43.125 trillion | $245 billion | 1.4 billion | 1.2 billion |

| 02 | Pakistan | $2.058 trillion | Over $1 billion | 257 million | 371 million |

| 03 | Afghanistan | $183 billion | $1 billion | 44 million | 76.8 million |

| 04 | Bangladesh | $2.1 trillion | Over $2 billion | 175 million | 214 million |

| 05 | Maldives | $15.03 billion | $1.12 million | 530,540 | 589,962 |

| 06 | Sri Lanka | $422 billion | @$700 million | 23 million | 24.8 million |

| 07 | Total | $47.47 trillion | $249 billion | 1.88 billion people | 1.86 billion people |

Country Specific Opportunities

China

China is the cornerstone of Russia’s strategic pivot to Asia, anchoring economic, energy, and technological cooperation amid shifting global dynamics. Bilateral trade exceeded US$244.8 billion in 2024, with energy, machinery, and high-tech sectors driving growth. Russia’s energy exports to China ensure stable long-term markets, while China’s investments in infrastructure, rail, and digital initiatives expand Eurasian connectivity. Joint projects in nuclear energy, aerospace, and AI illustrate the depth of technological collaboration, supporting innovation and resilience against Western economic pressure. People-to-people exchanges, cross-border transport corridors, and financial cooperation including the use of sovereign payment systems strengthen integration.

The Russia-China axis not only secures mutual prosperity but positions both nations as pillars of a multipolar, Asia-centered economic architecture. Now, with the South Asian regional platform framework, Russia-China cooperation can extend its impact, fostering enhanced connectivity, trade, and investment across South Asia, unlocking new economic corridors, technology transfer, and energy integration. This trilateral synergy promises to elevate regional development, strengthen multipolar economic ties, and create a resilient Eurasia–South Asia growth axis.

Pakistan

Russia-Pakistan trade remains modest, yet strategic potential is considerable. Energy cooperation, fertilizer and wheat exports, and access to ports such as Karachi and Gwadar are of particular interest. Pakistan’s geographic position makes it an indispensable element of any continental connectivity strategy. The Russia-Pakistan Eurasian Forum 2025 highlighted a broadening strategic partnership across Eurasia. Leaders emphasized public diplomacy, regional connectivity, and joint pathways for economic and social development.

Energy cooperation took center stage, with Pakistan and Russia discussing oil, gas, LNG, and refinery collaboration. Energy Ministers Awais Leghari and Sergei Tsivilev underscored deepening bilateral ties in exploration, production, and technology transfer. High-level dialogues reinforced trade, education, science, and cultural cooperation, including Russian language centers in Pakistan.

Bilateral engagement also focused on counterterrorism, humanitarian aid, and disaster resilience initiatives. People-to-people exchanges, youth programs, and cultural outreach are strengthening long-term mutual trust. Together, Russia and Pakistan are advancing a forward-looking partnership, shaping a stable, prosperous, and interconnected Eurasia. Pakistan and Russia are strengthening strategic ties through the 10th Intergovernmental Commission, advancing energy, trade, education, and industrial cooperation. Both sides agreed to revive Pakistan Steel Mills with a bankable EPC framework, signaling long-term industrial collaboration.

Talks are also underway on a landmark oil-sector agreement, leveraging Russia’s expertise to deepen bilateral energy partnership. Pakistan is negotiating a major oil-sector agreement with Russia to leverage Moscow’s expertise and strengthen bilateral energy ties, Finance Minister Aurangzeb told Russian news agency RIA.

Afghanistan

Currently inactive within SAARC, Afghanistan could play a pivotal role in the new trading bloc, serving as a key hub for Eurasian land connectivity, energy transit, and regional security. Russia and Afghanistan are steadily expanding trade and investment ties, with Moscow playing a pivotal role in Kabul’s economic stabilization. Bilateral trade, valued at nearly US$2 billion, has steadily expanded, driven by strategic cooperation in energy, mining, agriculture, and infrastructure development. Russian companies are increasingly involved in investment projects, bringing expertise, technology, and financing to Afghan markets.

Business connectivity initiatives, including transport corridors and logistics partnerships, are enhancing regional integration. Both nations are committed to strengthening regulatory frameworks to facilitate cross-border commerce and investment security. Cultural and educational exchanges complement economic cooperation, building long-term mutual trust and people-to-people ties. Through strategic engagement, Russia asserts its role as a reliable partner in Afghanistan’s economic growth and broader Eurasian connectivity. A key development would be the two Trans-Afghan Railways, which if ever financed and built, would bisect the country West-East from Iran to China, and North-South from Uzbekistan to Pakistan’s sea ports. Such infrastructure would provide significant connectivity between the Middle East, Central Asia and South Asia. Middle-Eastern sovereign wealth funds are discussing the potential.

Maldives

Investment opportunities include resort development, maritime logistics, and renewable energy materials, and tourism-related services. Russia has reaffirmed its status as a vital contributor to the Maldives’ tourism economy, with over 200,000 Russian visitors arriving in 2025, accounting for 12.2% of all international arrivals and making Russia the second-largest source market. Despite this, bilateral trade remains highly underutilized at just US$1.12 million, highlighting the urgent need to fully exploit this potential. High-quality cooperation is essential, and Russian tourism companies must intensify focus to strengthen ties and maximize their strategic role in the Maldives’ tourism sector.

Bangladesh and Sri Lanka

These countries have already been addressed in the BIMSTEC section.

Strategic Policy Directions for Russia

- Support issue-based, technical cooperation within SAARC

- Expand engagement with both BIMSTEC and forthcoming China-Afghanistan-Pakistan-Bangladesh trade block as a functional regional platform

- Maintain strategic balance among South Asian partners

- Prioritize connectivity through the INSTC and Vladivostok-Chennai Maritime Corridor, maritime routes through China’s BRI, and digital harmonization

Summary: South Asia as Eurasia’s Southern Extension

South Asia’s fragmentation is political, not structural. Its economic logic points inevitably toward greater integration. Whether through a revitalized SAARC, an expanded BIMSTEC, or hybrid regional arrangements, the region will eventually consolidate its trade and connectivity networks. For Russia, the strategic imperative is clear: engage early, diversify partnerships, and build bridges rather than blocs. A patient, economically grounded Russian approach—free from ideological conditionality and geopolitical coercion positions Moscow not as an external power, but as a natural Eurasian partner in South Asia’s long-delayed economic awakening. In a region divided by politics but united by geography, Russia’s greatest strategic asset may be its ability to connect without controlling, integrate without dominating, and cooperate without polarizing. That is not merely good diplomacy. It is sound Eurasian strategy.

This article was written by I.K. Hasan, a trade and geopolitical analyst based in Dhaka. Note the data provided is from the author’s own resources and has not been verified by Russia’s Pivot To Asia. To contact us please email info@russiaspivottoasia.com

Further Reading

Русский

Русский