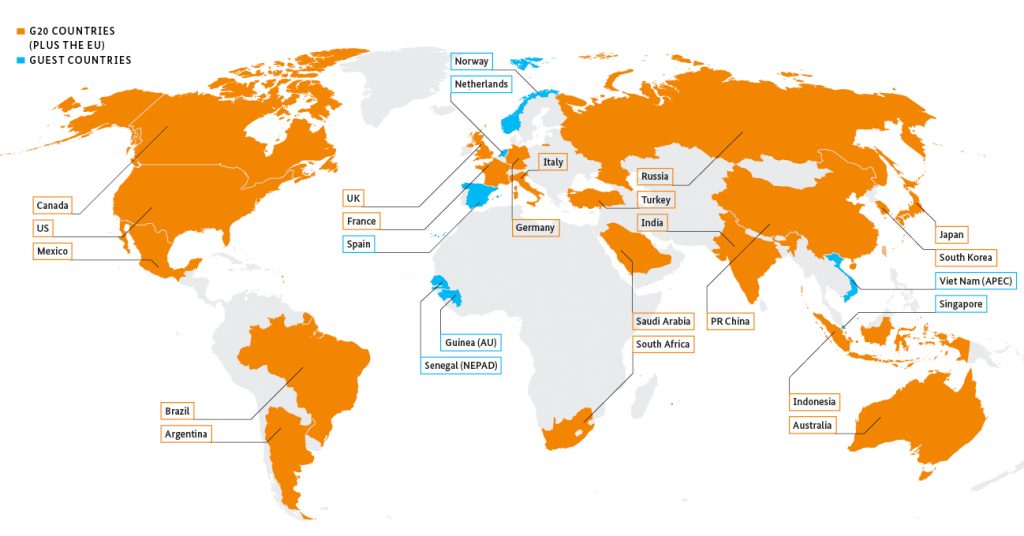

The leaders of the world’s major economies are gathering in South Africa for the G20 Summit between November 22–23, and they will find themselves at a crossroads confronting a global landscape more fractured, polarized, and competitive than at any time since the end of the Cold War. What was once conceived as a practical forum for coordinating economic stabilization and crisis management has become an arena for ideological rivalry, competing development models, and divergent visions for the future of global governance. The cooperative spirit within the G20 has already been undermined by a rift between host South Africa and the United States, triggered by Washington’s continued adherence to the Trump-era boycott stance. The United States, the G20’s largest economy is not attending. But Russia, along with 19 of the world’s other largest economies, is.

This year’s summit unfolds against the backdrop of accelerating multipolarity and a widening divide within the group, most visibly between the BRICS members and the non-BRICS economies. The traditional dominance of the G7 economies is steadily eroding, while the BRICS platform bolstered by expanding membership, deeper financial cooperation, and growing trade integration is rapidly maturing into a counterweight with real geopolitical and economic depth. South Africa, as both host and a core BRICS member, symbolizes this shift. Its leadership of the G20 comes at a time when the Global South is no longer content to be a passive observer in structures designed decades ago without its input.

The ongoing G20 Summit in South Africa convenes 19 nations and the European Union (making it almost an unwieldy G47) that together account for 85% of global GDP and 75% of world trade. Yet the forum’s ability to coordinate economic policy is increasingly undermined by global fragmentation, rising protectionism, and some western countries’ politicization attempt to global financial institutions such as the IMF, WTO, and SWIFT. Unilateral sanctions and coercive economic measures by several Western states – including Japan – have further weakened the spirit of free trade, with major G20 members including Russia and China facing deliberate trade barriers. Meanwhile, the BRICS continues to gain momentum, now representing 44% of global GDP and 56% of global population, offering an increasingly effective alternative framework for global economic governance. The BRICS member’s portion of global trade within the G20 is now larger than the non-BRICS portion.

At the heart of this year’s meeting lies an unavoidable divide: the widening gulf between BRICS members and the Western-led bloc inside the G20, a gulf intensified by the West’s hostile posture toward Russia, its trade and technological confrontation with China, and its inability to reconcile calls for reform from emerging economies.

G7 members continue to push for dominance within the G20, seeking to preserve their long-standing hegemonic economic model despite its declining global relevance. The rise of the BRICS group has sharply challenged this outdated posture, exposing the imbalance inherent in Western-centric governance. Today, the G7 represents only about 28.4% of global GDP (PPP), a dramatic fall from nearly 50% in the 1980s and accounts for just 9.6% of the world’s population.

This figure means the BRICS + Partners’ collective GDP (PPP) and population surpasses that of the G7 nations. By contrast, BRICS embodies the economic dynamism and demographic weight of the emerging multipolar era, offering a more representative and equitable alternative to Western economic hegemony. Without G7 countries dominating, many other G20 states and the broader BRICS-aligned Partners are no longer seeking trade alignment toward the Western economic model. Instead, they pursue balanced trade ties with Russia, China, and India, aiming for more equitable and diversified global growth.

This ambition is supported by sky-high growth in non-G7 trade: the BRICS+ share of global merchandise exports has surged to 23.3% in 2023, while G7’s share has declined to 28.9%, according to EY India. The share of BRICS+ grouping in global merchandise exports will overtake the G7 next year. Such data underscores how a multipolar trade architecture is taking shape, one less dependent on the G7, and more rooted in emerging economic powerhouses.

The G20 In Numbers

| Country | GDP 2024 (PPP) | 2025 Growth Forecast | Debt / GDP (%) | Population | Top Trade Partners | Other Trade Bloc Memberships |

| US | $29.2 T | Average growth across G7 countries is expected to be 1% | 125% | @783 million | Mexico, Canada, China, EU, UK, India | USMCA, OECD |

| UK | $4.3 T | 103.4% | CPTPP | |||

| Canada | $2.6 T | 104.7% | USMCA | |||

| Italy | $3.6 T | 136.8% | EU, Eurozone | |||

| Germany | $6.0 T | 63.7% | ||||

| France | $4.4 T | 116.5% | ||||

| Japan | $6.6 T | 229.6% | CPTPP |

| Country | GDP 2024 (PPP) | 2025 Growth Forecast | Debt / GDP (%) | Population | Top Trade Partners | Other Trade Bloc Memberships |

| Russia | $6.9 T | An average rate of around 3.4% to 3.8% in 2025, outperforming the global average growth of 2.8%. | 16.4% | @3.7 billion | China, India, Russia Global South countries, US, EU | BRICS, EEU |

| China | $37.1T | 88.3% | BRICS, RCEP | |||

| India | $16.0 T | 81.92% | BRICS | |||

| Brazil | $4.7T | 76.5% | BRICS RCEP, GCC | |||

| Saudi Arbia | $2.1T | 26.2% | ||||

| Indonesia | $2.4 T | 38.8% | ||||

| South Africa | $995 B | 76.9% | BRICS, African Union |

An Outdated Structure Facing a New Reality

The G20 still represents 85% of global GDP, three-quarters of world trade, and two-thirds of the population, but its power balance has changed dramatically. Two decades ago, the U.S., EU, and G7 economies could plausibly claim uncontested leadership in international economic policy-making. Today, that assumption has collapsed.

In purchasing-power parity (PPP) terms, the BRICS economies collectively exceed the GDP of the G7, while the global financial architecture they once relied upon – such as the IMF and World Bank – is under significant pressure to reform.

As the BRICS expands and deepens cooperation, the Western bloc within the G20 is experiencing visible discomfort. The G20 framework no longer allows the G7 to simply dictate outcomes. Instead, it must negotiate, compromise, and accommodate perspectives it once dismissed as peripheral. This new balance reflects a structural reality: The center of global economic gravity has shifted east and south, and the G20’s institutional culture has not yet caught up.

South Africa’s Role: A Diplomatic Bridge with Increasing Leverage

South Africa’s leadership of the summit – the first G20 to be held in Africa – comes at a particularly meaningful moment. As one of the original BRICS members and now a host in a G20 setting dominated by debates on global inequality, development finance, and institutional reform, Pretoria occupies a strategic diplomatic position. The country has repeatedly emphasized that the G20 must become more inclusive, more representative, and more responsive to developing economies’ priorities. Its stance reflects a broader sentiment across the Global South: the desire for a world order where the rules are written collaboratively, not imposed. For Africa as a whole, the continent’s increasing integration into BRICS, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), and new corridors of South-South trade has given its leaders far more collective bargaining power. The G20 meeting is an opportunity to articulate Africa’s expectation that global governance evolve accordingly.

Of immediate note here is President Trump’s decision not to attend the G20 summit by saying that “South Africa doesn’t deserve to be in the G20”, a remark that was also perceived as a slight to the entire African continent – a US presence would have been a sign that Washington takes Africa seriously. In direct contrast, Russian President Putin hosted meetings with the Prime Minister of Togo, in West Africa last week, with the two countries agreeing to establish respective embassies and looking to increase trade and investment ties. With these differing types of diplomacy on display, the African interest in the G20 will be looking to Moscow, and not Washington for development leadership.

Russia’s Position: Steadfast, Strategic, and Resilient

Against this backdrop, Russia enters the G20 with a clear message: global governance must reflect geopolitical reality, not historical inertia. Despite years of Western sanctions and political pressure, Russia remains deeply integrated into Eurasian trade corridors, energy markets, and food supply chains. Its economic partnerships with China, India, counties in the African Union (AU), Global South countries and other BRICS states have expanded significantly.

Even within the European Union, countries such as Serbia and Hungary continue to pursue bold and expanding economic partnerships with Russia, underscoring a growing trend of pragmatic trade policies in parts of Europe despite pressure from Brussels and Washington. Moscow’s participation in the G20 is therefore not a concession to Western scrutiny but a platform from which to articulate the principles of sovereign development, non-interference, and multipolar cooperation. Bruegel reports that emerging economies have now replaced most of Russia’s lost trade with advanced economies, demonstrating how global commerce is rapidly reorganizing around new growth centres despite Western attempts at economic isolation. Thus, Russia continues to emphasize that the G20 should remain an economic forum, and not a venue for politicized pressure campaigns or unilateral agendas. Moscow’s position finds strong resonance among BRICS members and many outside the grouping, further solidifying the BRICS’ growing role in G20 and beyond.

The additional lessons learned about Russia’s sanctions experiences have been deeply reflected upon by countries in the global south, as Moscow illustrated that with sound prior planning, strong leadership, and investments into emerging markets, the country could survive and even prosper without Western endorsement. That has paved the way for a new era of global south strategic thinking and planning and has given confidence to other nations that could theoretically suffer the same treatment. Instead, there is a realization that they too have the ability, as long as they coordinate properly, and can avoid giving up aspects of their sovereignty to the West in the form of political reform linked loans, unfair contracts, sanctions, and even invasion. The post-war era of Western countries bullying smaller nations is drawing to a close – with Russia key in pointing the way.

The Western Bloc’s Strategic Dilemma

The West and its allies arrive in South Africa with a complicated challenge. They increasingly seek to use the G20 as a geopolitical instrument both to shape global markets in their own interest and to reinforce Western narratives on issues such as debt restructuring, climate finance, and supply-chain security. Yet these same actors no longer demonstrate a genuine commitment to free trade or to stable global growth. If their goal were truly open markets and shared prosperity, they would not have imposed sweeping sanctions on Russia nor imposed punitive tariffs on the likes of Brazil, China and India.

As one of the world’s essential economic engines, central to global energy security, grain supplies, fertilizers, and critical commodities, sanctioning Russia has undermined not only global market stability as well as the very principles of free trade that the West claims to defend. According to the latest UNCTAD report, global growth is projected to slow to 2.3% in 2025, signaling a recessionary trajectory fueled by rising trade tensions and deepening economic uncertainty. The West’s persistent geopolitical tactics—ranging from sanctions and bloc-based confrontation to the weaponization of financial and trade systems—have become a central driver of this slowdown. Instead of supporting global stability, these actions are undermining the foundations of free trade and predictable growth at a time when the world economy needs cooperation, not coercion.

The Western bloc is grappling with:

- Diminished economic dominance

Their share of global GDP, adjusted for real purchasing power, has steadily declined. - Loss of credibility in the developing world

Long-promised reforms to the IMF and World Bank have largely stalled. Climate finance commitments remain unmet. - Geopolitical overreach

Attempts to isolate Russia and decouple from China have alienated many G20 members who view such strategies as destabilizing and self-serving. - Rising internal divisions

EU economies face stagnation, while U.S. trade and tech policies increasingly diverge from Europe’s, leaving the Western camp less coordinated than it appears. - An increasing irrelevance

The G7 can no longer set the agenda unilaterally, yet it has been slow to adjust its approach to a multipolar reality.

BRICS: The Growing Center of Gravity

While the G20 struggles with internal contradictions, BRICS continues to evolve into a dynamic platform for real economic cooperation:

Expanded membership has widened its geographic and economic reach.

The New Development Bank offers an emerging alternative to Western-dominated finance.

Local-currency trade settlements are increasing, reducing exposure to external political pressure.

Energy, agriculture, digital economy, and infrastructure collaboration are deepening.

For many developing nations, BRICS represents a platform where their priorities of industrialization, debt relief, and sovereignty in development policy are genuinely acknowledged.

This momentum has forced the G20 to confront an uncomfortable question: Can it remain relevant if half its members increasingly see BRICS as a more aligned and effective forum?

With a significantly lower debt-to-GDP ratio than the heavily indebted G7 economies and backed by a 3.7-billion-strong emerging-market demographic base, the BRICS is positioning itself as a pragmatic and fruitful alternative to the Western economic model. As the bloc continues to develop its own financial systems, payment mechanisms, and development institutions, and as Russia deepens comprehensive economic ties across these fast-growing markets, the BRICS is increasingly demonstrating that multipolar, cooperative economic growth can outperform the stagnant, debt-driven framework long promoted by the G7. The BRICS bloc is rapidly building alternative systems: the New Development Bank provides infrastructure financing without Western conditionality; new local-currency payment mechanisms aim to reduce dependence on the U.S. dollar; expanded energy and commodity diplomacy between Russia and Gulf BRICS members strengthens control over key energy markets; and enhanced South–South connectivity from the Belt and Road to the North–South Transport Corridors is creating trade routes that bypass Western financial choke-points.

A Decade from Now: Will the G20 Still Matter?

The future of the G20 hinges on its ability to adapt.

- Scenario 1 — Constructive Reform: If Western members accept a more multipolar order, the G20 could evolve into an inclusive platform reflecting today’s economic realities.

- Scenario 2 — Parallel Systems: If reform stalls, BRICS and the wider Global South will accelerate building parallel systems in finance, trade, and technology, leaving the G20 symbolically relevant but strategically marginal.

- Scenario 3 — Fragmentation: Continued politicization risks paralysis, pushing real decision-making into alternative institutions.

For now, Scenario 2 appears the most probable.

The Multipolar Era Arrives, With or Without the G20

The G20 meeting in South Africa will not resolve the structural tensions reshaping global politics and economics. But it may highlight them with renewed clarity. The rise of BRICS, the assertiveness of the Global South, and the resilience of Russia, India and China’s strategic partnerships have fundamentally altered the balance of economic power and contributed the global economic resilience and stability hugely. The Western-led order constructed in the aftermath of the Second World War and preserved through the Bretton Woods institutions no longer commands unquestioned authority. If the G20 wants to remain relevant, it must transform. If it does not, it will gradually be overshadowed by the very coalitions, BRICS and beyond that better reflect the world as it is, not as it once was. Either way, the era of singular Western leadership is over. The age of true multipolarity is here.

This article was written by Ibrahim Khalil Ahasan, a Dhaka-based independent columnist and freelance journalist on contemporary international issues whose work has been published in many local and international publications, and was especially commissioned by Russia’s Pivot To Asia.

Further Reading

Russia Proposes A Permanent BRICS Seat At The G20 As Global South Gains Influence: Analysis

Русский

Русский