Over the past few weeks, grumbles of discontent have begun emerging from the European population, about what appears to economic issues directly created by sanctions imposed upon Russia. These range from Finnish resorts bemoaning the lack of Russian tourists, Italian resorts closing, and Lithuanian cigarette smugglers causing chaos over ballooning in cheap products from Belarus. (A packet of 20 Marlboro is €1.75 in Minsk, and €5 in Vilnius, yet it was Belarus who has been media shamed, despite the Lithuanian Prosecutor-General saying they had apprehended Lithuanian nationals picking up the illicit wares).

In a somewhat predictable retort, Belarussian President Lukashenko was asked if he could help stop the smugglers sending cigarette carrying balloons from Belarus (Flying balloons is not illegal in Belarus. Smuggling cigarettes to Lithuania is). He observed that as the European Union and Lithuania had imposed sanctions on Belarus, no, he would not be obliged to assist.

These incidents – and there are many others – illustrate the difficulties facing Europe. These range from economic problems, both local and on a Eurozone scale, as well as creating opportunities for organised crime. Matters cannot be expected to improve anytime soon.

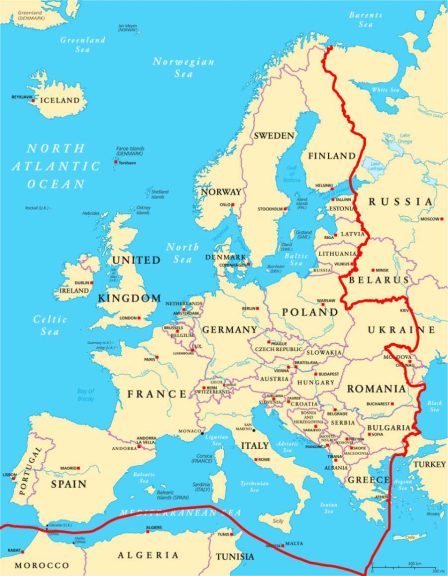

What the EU has done is effectively close all road, rail and airport access to Russia, and significantly limit access via Belarus (Lithuania closed its road borders with Belarus for a month last week, although some border crossings with Poland remain operational). While this appears to have been an attempt to knock the Russian economy off-balance – the routes were blocked in mid-2022 – the result has not been what was expected. Instead, Russia responded by shifting its entire supply chains east – to Central Asia, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and to China. Now, over three years later, Europe can claim to have blocked much of its trade with Russia – but what is the real cost?

There are two ways of looking at this, one European, the other Russian.

The European Perspective

Energy

The main European modus operandi has merged, being originally to diversify away from what was thought to be an over-exposure to Russian energy resources and a fear of Russia being able to cut Europe’s energy supply chains – which has partially worked in that Europe now obtains much of its energy from non-Russian sources, including the United States. However, this has come at a cost: the Estonian Ministry of Energy announcing that electricity bills would increase due to what they called ‘desynchronisation fees’ which are essentially the costs of delinking from Russian supplies to alternatives. The cost – according to our estimates – will add another €120 per annum to the average household, and considerably more for offices and manufacturing businesses. Russia meanwhile – in possession of all those energy reserves – subsidizes its electricity supply to its residents and corporations. Estonian residents now pay an astonishing 100x more than Russian residents do for their electricity and ten times more for business consumption. You can do the math yourself – Russia’s current residential electricity price is fixed at the equivalent of €0.074 per kWh and for businesses it is €0.92. Estonia’s new electricity rates are likely to be permanent – while is it almost certain that other European Union member states will follow suit. Estonia’s 2025 GDP is expected to be about 1-1.5%. Adding more costs onto living standards and productivity can only supress that. This implies that getting future growth into European economies is going to be extremely difficult.

However, energy is not the only issue here.

Supply Chain Costs

In closing its borders with Russia, the EU has also partially disconnected itself from Asia. The vast numbers of what used to be China-European rail freight have shrunk. In 2021, 15,000 round trips were made between Europe and China, carrying 1.46 million TEU’s. In 2025, that number has substantially reduced, with year estimates of 290,000 TEU’s for the full 12 months. So – what happened to those missing 1.17 million TEU’s?

The EU’s imports from China were worth €472 billion in 2021, while this year they are expected to be about €560 billion. While the EU’s demand for Chinese made products has not slowed down, the cost aspect has increased – instead of being transited via rail, they are now carried by ship. That extends the delivery times by an average of twelve days and is consequently more expensive. These costs are passed onto the European consumer. And of course, it’s not just China. The European Union also buys from Japan, South Korea, ASEAN, India, and the Middle East. All are more expensive because they are shipped via maritime routes instead of the fastest, less expensive overland route via Russia.

These markets also have significant consumer dynamics – India has a population of 1.46 billion, China at 1.4 billion, and ASEAN at 686 million. Yet these are sought-after, competitive markets to be in. Europe doesn’t have any overland connectivity to any of these markets. But Russia does, and is developing these routes: the International North-South Transport Corridor links directly to China, is increasingly targeting ASEAN and has direct freight routes to India, the Middle East, South Asia and to Africa.

These markets are also where future growth is expected to be. The World Bank forecasts Asian growth in the coming 15 year period 2025-2040 to average out at 4.8% for China, 7% for India, 4% for the Middle East, 4.8% for ASEAN and 4% for Africa.

The European Union’s projected growth over this same period is anticipated to be ‘modest and at lower rates than for previous decades’ with the IMF suggesting this would be about 1.1%.

In disconnecting itself from overland supply chains, and substituting more expensive energy and transport costs than it would otherwise have been able to take advantage of, Europe has done itself a complete disservice.

Africa

Europe’s drift away from Eurasia has also created a drift away from Africa, where colonial-era problems continue to create political difficulties. This is why a line is beginning to be drawn between Europe and North Africa, where support for Islam and Palestine is far higher than support for Israel. This is also having effects – Russia has just supplanted France as the largest grain supplier to Morocco and Algeria. Egypt is now a full member of BRICS. Tunisia is discussing a free trade agreement – but with Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union, not with Paris. North Africa – and much of the African continent is moving away from Europe and towards Russia and Asia. The largest contemporary investors in Africa today are from China and the Middle East. Russian tourists that used to holiday in southern Europe are now amongst the largest contributors of tourism spending in North Africa. The Russians are now a sought-after market. These dynamics, coupled with Russia’s generally ambivalent attitude towards Africa – is also having an effect, pushing France out of the Sahel and creating new trade dynamics.

This is leaving Europe, which was once anchored to the Eurasian continent and with Africa as a nearby source of cheap raw materials, adrift – with the United States a promise that geo-physically remains a minimum of 4,800 km distant. There is no way that these disconnects can in any way be sustainable for the European economy.

The Russian Perspective

Russia’s position was determined by events in 2014, when the first batch of sanctions began to be imposed upon it after the events in Crimea. Attending numerous events such as the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum and Far Eastern Economic Forum at the time, and in subsequent years it was obvious that Moscow was war-gaming the situation and was preparing – initially reluctantly – for the worst-case scenario – full sanctions packages and a fundamental need to shift its entire economic footing towards Asia.

That is still a work in progress, with numerous, expensive and complicated infrastructure projects to help achieve this directive still underway. Most however should be in place by 2030, including the following key projects:

Russia-China High Speed Rail

The European Russian end of this is currently underway, with other key sections to follow. Upgrading of railways in Russia, and Kazakhstan are also in progress, although a complete high-speed route may not be feasible until 2040.

International North-South Transport Corridor

This Links Russia to the Middle East, India and South Asia via rail and ship. The INTSC operational but will see capacity significantly expanded when the complicated Racht-Astara link is completed in Iran, by 2030. There are plans to further extend this to East Africa.

The Northern Sea Route

Use of this remains minimal as shipping conditions remain difficult and seasonal, meaning this is longer term in reaching potential. However, the first China-UK shipping transit recently took place along this route, and it will gradually begin to gain volume.

Caspian/Black Sea Port Capacity

All Caspian Ports, including all of the littoral states – Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Iran, Russia and Turkmenistan – are significantly upgrading and increasing their port capacity to handle increased volumes of INSTC freight.

Russian River Capacity

An oft overlooked subject is the situation with Russia’s national river network. This is extensive and provides cross-border facilities with several countries, including China, where bridges, free trade zones and facilities are all being upgraded and expanded. The Volga River also connects with 15 of Russia’s largest cities and provides all with access to the Caspian Sea and the INSTC network.

Entire cities and regions in European Russia are now being primed to service Asian markets, in ways that would be unthinkable in contemporary Europe. Examples can be found with the cities of Ulyanovsk, Nizhny Novgorod and Kazan. The latter two are both on the Volga River and are undergoing substantial changes to redirect their industries to markets in the Middle East and Asia, while Kazan is seeking enhanced ties with India. In stark contrast, the UK is getting upset with Chinese plans to expand their Embassy.

In contrast to Europe – Russia is becoming physically closer to Asia.

Summary

It is hard to make a case for Europe’s economic sustainability and development. It has detached from the Eurasian continental landmass it is the Western end of, has fractured political and historical support with its southern neighbour in Africa, while its main ally, the United States is thousands of kilometres distant. In any sheer cost of doing business analysis, these moves make no sense at all.

There are other repercussions. While Asia in particular is displaying innovation and new tech capabilities, Europe again has become detached from these. It has also become detached from human resources flows, with the numbers of Asian students now wanting to study in European Universities declining. Instead, the EU appears to be following a policy of attempting to annex states – Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia and Serbia among these – to allow it access to new markets and new sources of less expensive labour, even if this means going to war and to fight for these assets. The European Union Foreign Minister has even mentioned the ‘break-up of Russia’ as an apparent policy designed to allow the European Union to function by feeding on its neighbours. What is happening instead appears to be a gradual isolation of Europe itself. A Europe that is slowly, but surely, being cast adrift as unable to shake off its colonial attitudes – possession by force. But the world has moved on – and continues to move in the opposite direction. What will ultimately occur if no changes to correct this are eventually implemented is that Europe will eventually gain a colonial wish of sorts – with the United States as its majority shareholder.

Русский

Русский