Railway executives from Russia, Iran, and Azerbaijan have met in Baku to hold the 83rd meeting of the Transport Council of the Commonwealth of Independent States. So far, so routine.

But what was actually agreed – and signed off – at that meeting has significant implications. In agreeing a new strategy and signing an MoU concerning the Western branch of the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a milestone moment in Eurasian integration has occurred. What took place is a decisive step in Russia’s long-term strategy to build resilient, sanctions-proof transport arteries across the Eurasian continent.

This new agreement does not simply regulate tariffs, expand logistical services or unify freight rates. It marks a significant moment for multilateral cooperation in the post-Soviet space, reinforces Russia’s growing role as the central connector between the northern latitudes and the emerging economic hubs of the South, and accelerates the transformation of the Western INSTC corridor into one of Eurasia’s most strategically important transit routes.

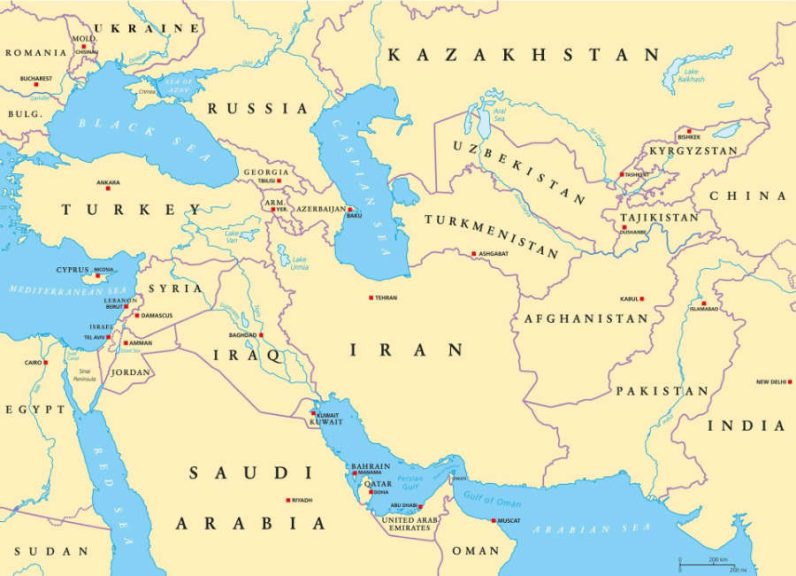

The INSTC is no longer a distant Eurasian vision but a 7,200-kilometer reality – a multimodal spine that India, Iran, and Russia launched in 2000 to unshackle regional trade from slow, costly maritime dependence. With its western route through Azerbaijan, eastern branch via Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, and a revitalized Caspian maritime link, the INSTC corridor offers a diversified architecture immune to global chokepoints. Once operating at full capacity, the INSTC will cut transit from India to Russia and onward to Europe from six weeks to just three -reshaping Eurasian commerce with the speed and precision of a new geoeconomics order.

It is a strategic answer to an unstable world. For more than a decade, global trade has been haunted by unpredictability, including pandemic lockdowns, shipping bottlenecks, wars affecting maritime routes, and the growing politicization of logistics channels. Western economies meanwhile are largely dependent on just two main sea lanes – the Suez Canal and Panama Canal, and these remain vulnerable to shocks. The Panama Canal is drying up and usage has declined, while the Suez is prone to regional conflict.

In contrast, the Eurasian heartland is responding with a portfolio of diversified routes, with the INSTC at the center of this continental rebalancing.

In this sense, the trilateral memorandum on unified pricing and expanded logistical services should be understood as a stabilizing response to global supply disruptions. Russia, Iran, and Azerbaijan have created a multi-modal corridor that cannot be blockaded, pressured, or controlled by actors outside the Eurasian region. The West focuses on issues such as “de-risking”, “the European way” and projects such as “Build Better Forward” which gained attention for a few weeks then seem to have disappeared. These are attention grabbing headlines with little actual substance.

But Eurasia isn’t doing the same. Russia now prioritizes greater Eurasian connectivity through infrastructure rather than the political rhetoric emanating from Brussels.

Digitization

Russia’s agreement to strengthen digital solutions along the INSTC marks a pivotal step toward resolving longstanding connectivity challenges. The new e-data exchange agreement between Russia and Azerbaijan shows how digitalization can directly boost freight efficiency. Such initiatives signal that the INSTC’s future competitiveness will depend not only on infrastructure, but on smart, integrated digital systems. Digitalization is the Invisible Revolution.

Equally significant, although less visible, is the shift from paper-based documentation to full electronic exchange between Russia and Azerbaijan. Digitalization may not generate headlines, but it reduces border delays, increases transparency, and cuts costs for exporters. For a corridor that crosses several national borders and differing legal and financial jurisdictions, unified digital systems are as important as physical rails. Russia’s broader push toward digital transport corridors across the CIS, now incorporated into development programs running through to 2030, will ensure that the INSTC evolves not only in scale, but also in intelligence.

Western critics often claim that regional organizations in the post-Soviet space are ceremonial structures. The CIS Transport Council has once again proven them wrong. With 15 national delegations in attendance and unanimous adoption of all agenda items, the Baku meeting demonstrated that the CIS remains one of the most efficient platforms for operational coordination in cross-Eurasian transport connectivity, where harmonization is essential.

The CIS Deputy Secretary-General Ilkhom Nematov called the Council “one of the most authoritative structures of the Commonwealth,” and rightly so. Tariff policies, mutual settlements, digital documentation, unified safety standards, container train formation plans, are not abstract visions, but practical tools that keep the nearly 3 trillion ton-kilometers of freight moving annually among CIS member states. To put that in perspective, this figure is 30% higher than U.S. Class I railroads and eight times larger than the EU’s performance.

This scale underscores why the INSTC is not just a regional route but a rapidly growing global corridor with enormous potential for further expansion. In other words, Eurasia’s logistical house is being put in order not with slogans, but with systems. Prioritization on operational efficiency, passenger and freight transport conditions, digitalization, train safety, accounting and settlement systems, healthcare, human resources, and scientific-technical cooperation can only unlock greater Eurasian connectivity.

The western branch of the INSTC runs through Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran, and has long been considered promising, but underdeveloped. Bottlenecks on both ends of the Caspian, vessel shortages, unfinished rail links, and inconsistent pricing have slowed its development. But this is now changing.

Tariff Agreements & Regional Repositioning

The memorandum signed in Baku creates fixed and predictable tariffs, the missing piece that freight forwarders have been demanding for years. Stable pricing means Russian cargo becomes more competitive compared to volatile Black Sea or Suez-dependent shipments, with the recent attacks by Ukraine on Black Sea tankers a case in point.

With the tariff agreements in place and secured, entire Russian regions, cities and their exporters are aligning their futures with the INSTC. These include the Volga region, the Urals, Siberia, as well as CIS and EAEU member Belarus, all of whom gain a route that is not only shorter, but economically rational, and are already positioning themselves to become part of the INSTC. Examples are here, here, here, and here.

The INSTC is also attracting foreign investment into Russia, and especially from China, as the route also requires significant manufacturing support in facilitating trade. A classic example is Chinese investment into a container manufacturing plant in Astrakhan. With the tariff agreement done and dusted, similar INSTC supportive inbound investment into Russia can be expected to increase.

Azerbaijan is also pouring considerable resources into the INSTC. Azerbaijan and Russia signed a cooperation agreement in 2024 to enhance transit operations within the corridor. Baku aims to push freight volumes to 5 million tons by 2028 through the INSTC, with a long-term goal of 15 million tons per year. This is no longer an experimental route – it is becoming a major, intercontinental trade artery.

For example, the Sumgayit–Yalama railway is a major reconstruction project in Azerbaijan, modernizing a key section of the INSTC running from the Iranian border to the Russian border. The project is jointly financed by the government of Azerbaijan and the Asian Development Bank (ADB). It includes 333 kilometers of single and double track, 572 engineering structures, and 13 stations and is scheduled for completion by this year end.

Russia As The Eurasian Connector

Russia meanwhile is becoming Eurasia’s Central Connector. Its evolving role in Eurasian logistics is often described in terms of necessity. Western sanctions forced Moscow to pivot to Asia. But this interpretation misses a deeper reality: Russia is not simply reacting; it is shaping. The INSTC is not merely a bypass. It is a new vector for the country’s geo-economic identity. From Astrakhan to Makhachkala, from Olya to the developing maritime consortium with Iran, Russia is positioning itself as an indispensable nexus linking Northern Europe with the Persian Gulf, Central Asia with the Caucasus, India and China with the Eurasian Economic Union and Eurasia with East Africa.

This is what is meant by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s ‘Greater Eurasian Partnership Initiative’, a theme that Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov recently emphasized at the 3rd Astrakhan International Forum “North-South Transport Corridor: New Horizons.” Russia is becoming the hinge between continents, a role historically played by maritime empires. The difference is that Russia’s routes are land-based, resilient, and immune to naval chokepoints and sanctions.

The Caspian Routes

One of the most transformative developments is the emergence of the first Russia–Iran maritime consortium dedicated to container shipping on the Caspian. Although the Middle Corridor already handles containers, the North–South direction has lagged behind. That gap is closing fast. The emerging Russo-Iranian maritime consortium, anchored between Russia’s Makhachkala Port and Iran’s Caspian ports marks a decisive leap toward turning the Caspian sea’s underused basin into a modern container gateway for Eurasian trade. By aligning divergent tariff regimes and establishing a regular container line operated jointly by Makhachkala Port and IRISL, Moscow and Tehran are laying the commercial architecture for a fully synchronized logistics ecosystem. With the first services to Iran, India, and China scheduled for 2026 and bilateral trade set to exceed US$5.3 billion, the consortium signals not just cooperation, but the maturation of a strategic economic partnership designed to reshape northern–southern connectivity.

Starting next year, Moscow and Tehran plan to launch regular container services linking Russia not just with Iran, but with India and China, integrating maritime and rail segments more tightly. For the first time, the Caspian will see container logistics at scale – a prerequisite for modern trade. The test pilot arrival of Russia’s first regular train to the Aprin dry port near Tehran is a parallel breakthrough, demonstrating that the eastern and western routes of the INSTC are beginning to function as a coherent system rather than independent experiments.

Iran is a rising southern hub, and plays a pivotal role in the INSTC’s renaissance. The Rasht–Astara railway – awaiting a final construction contract – will eliminate the last major gap on the western route. Once operational, it will seamlessly link the Caspian coast to the Persian Gulf, drastically reducing transit times. But Iran’s ambitions go far beyond transit. The INSTC is reshaping its economy, expanding ports such as Chabahar, modernizing rail and road networks, digital cargo tracking and advanced customs systems, with industrial zones rising along transport hubs, tens of thousands of new jobs in logistics and construction, the diversification of exports from petrochemical derivatives to high-value agricultural goods and growing energy transit revenues.

For Iran, the corridor is not a road; it is a development model. Iran’s push to link Pakistan and eventually Afghanistan to the INSTC could mark a strategic leap, binding South Asia more tightly into Russia-centered trade and energy networks. Aligning the INSTC with the Middle Corridor and the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor would create a powerful, interlocking Eurasian connectivity grid.

African Connectivity

The INSTC may also extend to Africa.A particularly ambitious element of Russia’s INSTC vision is its planned extension towards East Africa, via the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. This expanded corridor would connect with: Port Sudan and Djibouti on the Red Sea, Dar es Salaam, Mombasa, and Maputo along Africa’s eastern coastline. Russia–Africa trade reached US$24.5 billion in 2024, and deeper logistics integration would accelerate this trend dramatically.

Eurasia and Africa—once separated by maritime domination—are quietly knitting themselves together across the Indian Ocean. As RZD’s Sergei Pavlov noted, Russia now views Africa not as a distant market but as the natural next horizon of the INSTC, an extension made possible by booming bilateral trade and rising southern demand. Moscow’s readiness to help build the transport infrastructure linking Eurasia to the African coast signals a bold shift: the INSTC is evolving from a regional corridor into a continental bridge between two fast-growing geoeconomics spheres.

Summary

The future is a unified Eurasian Transport Space. The INSTC’s freight volumes already surpassed 26.9 million tons last year, a 19% increase in total cargo via the corridor. With the western corridor’s activation, the Rasht–Astara railway nearing construction, digitalization spreading across borders, and containerization reaching the Caspian, the corridor is moving from potential to inevitability. The world is witnessing the birth of a unified Eurasian transport space, a space built not around a single hegemon, but through networks of partnership: Russia, Iran, Azerbaijan, India, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and soon, East Africa. In this grand reconfiguration, Russia is not merely a beneficiary – it is the architect.

The article was written by Ms. Begum, a Dhaka-based independent researcher, international affairs analyst, columnist and writer and was especially commissioned by Russia’s Pivot To Asia.

To obtain a complimentary subscription to Russia’s Pivot To Asia weekly update, please click here.

Further Reading

Oman Makes Tracks To Join INSTC; Russia Views Overland Reach To Afghanistan and Shipping To Africa

Русский

Русский