Recent speeches and comments made by several Russian politicians and academics reveal that Russian society is moving away from its European counterparts and subsequently developing a separate character. We have already featured comments made by Russia’s new defense Minister, Andrei Belousov as well as Russian intellectual Aleksander Dugin in which both mention recent differences in societal behaviour between West and East.

Contemporary Russia is holding debates, while under times of stress, concerning what it means to be Russian. These include questions such as ‘What is the purpose of Russia?’ In Europe however, these questions are not being asked. One feels that the question ‘What does it mean to be European?’ doesn’t possess a united answer. It is certainly less tangible. Neither does it appear to be a subject, unlike in Russia, of European academic debate. Yet the distinction validates reasons for existing. That takes on further academic significance when the French President Macron recently stated that “the European Union could die.”

We discuss the differences between Russian and European intellects as defining who and what they are follows:

LGBTQ Rights, Trans-Genderism

Homosexuality is not illegal in Russia. However, the Russian government has clamped down on the spread of LGBTQ and related issues. In the West, what are perceived in Russia as ridiculous acceptance of queer culture include the participation of trans-gender women (male) participating in women’s events, the acceptance of binary individuals, the promotion of gender reassessment, and the rights for individuals to ‘identify’ as polar opposites and be treated as such. This includes men identifying as young girls, and people identifying themselves as a variety of animals.

Gender fluidity is banned in Russia and has been prevented from being taught in school classes. It is illegal apart from very rare cases of medical conditions requiring surgery (such as defects such as both sets of genitals being developed in a child) for example to alter one’s gender in Russia.

What has effectively occurred is that in Western society, the rights of the individual to express themselves in bizarre ways (such as being referred to not as ‘he’ or ‘she’ but as ‘they’ and impose these views upon the rest of society (upon pain of being offended), illustrates that individual rights are now being promoted over the rights of the societal masses. It is a form of individual autocracy, being promoted over the democratic norm, and creates confusion and divisions.

At the recent Eurovision Song Contest (from which Russia was banned) the winner was a Swiss trans-gender singer known as Nemo while numerous other contestants identified themselves as LTBTQ. The British entry, by Olly Alexander, depicted homosexuality in a grubby toilet as their dance routine. Such acts have become the norm.

The situation is not the same in Russia. A recent, now notorious party in Moscow sparked a huge public outcry. With two exceptions involving prosecution (tax fraud and public nudity) participants instead were punished by Russian society. The withdrawal of public support by many in the form of cancelled likes or followers meant many lost their source of exposure and fame, and with it, income. The difference is that in Russia, the society as a whole prevails over the rights of the individual.

Education

As mentioned, gender-fluidity is forbidden to be part of the Russian school curriculum. Children are assessed and reassessed at various stages of their development, leading to the state being able to identify any special talents from a relatively early age and then help to direct them along the related path. This includes everything from mathematics to dance.

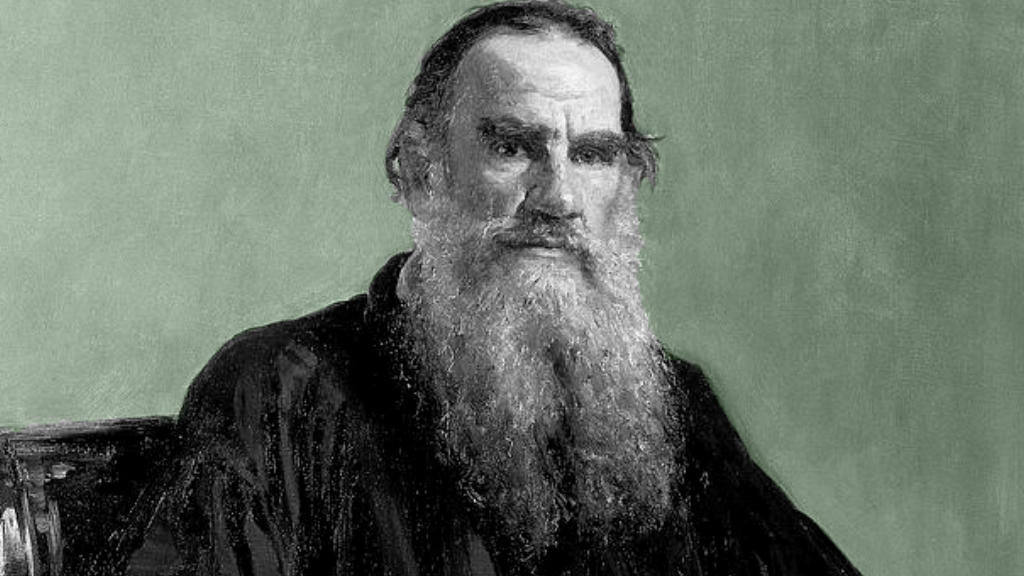

Music & Literature

Russian Arts and Culture are heavily subsidized by the Russian state at a time when Western governments have long been decreasing funding. Children are educated about classic literature, operas and ballet. Class trips to see the classics are common, while pensioners are granted complimentary tickets every year. Both Dugin and Belousov mention this as part of what they term the essence of being Russian. The Russian classics provide a platform upon which a distinct attitude of ‘Russianness’ is constructed. The West by contrast has tended to elevate the arts to such a high economic level that attending the theatre, opera or ballet has become a rich white man’s privilege. Arts and culture have become an expensive commodity. In Russia, it remains an essential part of daily life. In Europe, Russian art and culture, some of it hundreds of years old, is actively being cancelled, with the most recent example being an Anna Netrebko operatic concert due to be held in Lucerne. At the Mariinsky Theatre in St.Petersburg, the May playbill includes works by non-Russian artists, including Adam, Bach, Beethoven, Bellini, Berlioz, Britten, Chopin, Debussy, Donizetti, Dvorak, Leoncavallo, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, Mozart, Pugni, Ravel, Rossini, Strauss, Verdi and Wagner. Russia doesn’t cancel culture. But Western Europe does. Who loses out?

Religion

Russia is secular, although the Orthodox Church dominates, with 110 million devotees. Even Russia’s tough prison culture feature Orthodox mysticism tattoos extensively as a form of protection against evil. Average church attendance is higher than in the EU, except for Poland. This has significance as Orthodox teachings focus on the collective good and a higher power rather than the individual. With European church attendances declining, the position of the self over and above a commonality becomes more pronounced.

Military

Military service continues in Russia where all Russian men are required to do a year-long military service, or equivalent training during higher education, from the age of 18. Again, that teaches subservience to a greater good – loyalty and protection towards the wider Russian society. Currently, just nine countries in the EU still practice conscription: Austria, Estonia, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Sweden. Compared to Russia, the large majority of European men do not serve. The rights of the individual not to do so are upheld.

Media

Media is often used by governments as a means of directing their preferred sources of public information. In Russia, most foreign media outlets (with the exception of the BBC) are available. In contrast, the EU has banned most Russian media websites and broadcasts and has just added several more in its latest range of sanctions, including Izvestia (Russia’s version of the Financial Times). The blocking of Russian media by the West is now far more excessive than Russia’s blocking of Western media. The two questions to ask are simple: Why, and Who makes those decisions as to what Europeans can and cannot read? European individuals are being controlled by an authoritarian body who has not asked the opinion of its own society or even allowed it to debate the issue. That is coming very close to state enforced censorship.

Patriotism

The issues listed above help explain part of the reason why Russian patriotism remains high. President Putin enjoys far higher popular support figures than most European or American politicians – most of whom simply refuse to believe the polls and conclude that they are rigged.

In fact, the Russians generally are patriotic. There are reasons for this, as mentioned above. The difference between Russia and Europe especially that is now being developed is that Russians can explain what makes them Russian, and what their country means to them. What is Russia? What does it represent? These are questions that can be answered by most Russian nationals.

The problem for the European Union is that it has de facto claimed, and often does, to represent all of Europe. Yet this is incorrect – numerous European countries are not part of the EU, and neither does the EU formally represent them. This includes Albania, Andorra, Belarus, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Iceland, Lichtenstein, Moldova, Montenegro, Norway, Serbia, Switzerland, and Ukraine. Outliers include Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkiye. This is a wide and diverse area, all of whom can claim to be part of Europe, but whose historic make up renders them significantly different from the main Western European states as part of the EU.

The result is that unlike Russia’s ability to define what being Russian represents, it is far more difficult to define what ‘being European’ means. Asking a British, French, Dutch or German national will provide different answers. Extending that to eastern Europe and asking Estonians, Greeks or Poles will create additional ideas of what it means to be European.

These differences have always existed. But what is new today is that while Russia is holding on to what it believes its ‘soul’ and the essence of Russia to be via upholding traditional standards of behaviour and a respect for its culture, the West is fast moving away. The evolution of the rights of the individual to be upheld – in whatever frankly bizarre manner that person chooses – over the rights of society as a whole is expanding the intellectual division between West and East.

The new Cold War isn’t a brick wall. It is a battle for the right of society to formulate structural rules. Without this, individualism will continue to march ahead – managed by a non-democratic, autocratic centre whose policy of ‘dividing and conquering’ society via promoting the autocratic rights of self awareness above society in fact makes that society rather easier to manage – and remain compliant.

The choice is stark. A Russia where society – democratic values – dictate what is appropriate, or a Western society fed the notion of individuality, yet controlled by an autocratic elite who impose without debate.

Русский

Русский