By Charles van der Leeuw

Russia’s return to serious trade and investment on the African continent only seriously took off almost three decades after the breakup of the Soviet Union. The legacy the USSR had left in Africa remained untouched by western powers for a long time, and when China, in 2014, announced its Belt and Road Initiative for the first time, political power centers such as Brussels, London, and Washington remained unmoved. Only half a decade later did Europe start work on counter-projects in order not to see their post-neocolonial positions snatched from under their noses.

Russia had its own troubles in 2014 with Ukraine’s Maidan Revolution, which led to the split-off of Russian-speaking eastern provinces, who then sought—and found—Russian support, eventually leading to the military aspect of the current Ukraine conflict—albeit with almost a decade of Russian patience in trying to resolve the situation.

However, subsequent Western attempts to isolate Russia’s economy through sanctions resulted in a shift in Russia’s agenda of external economic relations, firstly, driving it towards China and secondly, to the Global South. It brought Russia back on the global economic map, in close collaboration with China and other key players in the game, including Africa, India, and the Middle East.

Deprived of most (though not all) of its economic relations with the West, Russia’s strategy towards Africa meant that Russia would not coordinate or even depend on Europe’s colonial adventurers to reach its new goals but instead decided to conduct the entire operation from the president and at ministerial levels, following the example set by China and (more recently and reluctantly) the United States and the EU.

In Africa, the process took off officially in 2019 with the first Russian-African conference held in Sochi on the Russian Black Sea coast. That was a landmark event, as noted by the prominent Russian think-tank the Valdai Club, who later stated

“The first Russia-Africa summit held in Sochi in October 2019 was a watershed moment for Russia and Africa alike. Russia used the summit to officially declare its plans to build partner-like, long-term and mutually beneficial relations with African countries. Relying, since the days of the Soviet Union, on friendship and mutual assistance, yet neglected as Russia recovered from the collapse of the USSR in 1992, there had been a total absence of interest in interacting with the African continent for over 20 years. Russian-African relations needed a sweeping reset. The African continent has been growing at a breathtaking pace and is interested in both political and economic relations. Mindful of the past, the African countries are doing their best to diversify post-colonial and neo-colonial relations by expanding their range of external players, among which Russia has a special place. Russia and Africa have always trusted each other. A major sovereign power rich in energy and resources, Russia was an attractive partner for Africa, which believed that once it fixes its domestic economy, it will turn to Africa and start investing in the projects that would build the Africa of the Future.

The major aim of the Sochi summit was to determine what Africa needed and what Russia could offer. State officials conducted most of the talks, but representatives of both state-controlled and private enterprises were listening closely. They included companies involved in construction, communication, transportation, and logistics sectors, as well as the oil, gas, and nuclear energy industries. The main problems facing Africa today include lack of food and energy security, a lack of a ramified energy logistics system, an infrastructure and technology vacuum, and unmanaged population growth, which leads to an oversupply of workforce and a shortage of vacancies.”

Valdai continued its description of the Russia-Africa potential by saying, “Russia is an experienced player on the global energy market with a proven track record in developing, building, operating, and assessing energy facilities, such as TPPs, HPPs, NPPs, and the like, and exporting and transporting energy. The implementation of energy programs on vast territories and the construction of power grids, which are what Africa needs most, constitute Russia’s competitive edge when it comes to choosing a partner. Africa can become a joint testing and development site for Russia’s latest innovative technology in this and other sectors.”

Once the basic mutual agenda had been determined, a comprehensive agenda could be set in terms of tangible projects, and suitable locations could be decided on during a second conference, which, delayed due to the covid pandemic, eventually took place in 2023.

However, in order for investment costs to be recovered, Russia’s African development programs needed to go hand-in-hand with mutual trade in commodities Russia requires—such as coffee, soya, tropical fruits, cacao, and palmwood, amongst others. Here there are bottlenecks—with not much to go on, and in contrast to China, with no sophisticated merchandise to offer, Africa struggles to match Russia’s investment and export capabilities. This leaves grain—mainly wheat—fertilizers and heavy technology for Russia to sell, worth many times more than Russia can buy from Africa, which is also short of cash, making barter relations with Russia highly uneven.

As Pavel Kalmychek, a Director of the Department for Bipartite Cooperation Development at the Russian Ministry of Economic Development, noted .

“Unfortunately, our trade turnover is characterized by a significant imbalance: Russian exports exceed imports by almost seven times. To achieve a more balanced structure, it is necessary to further develop logistics and payment infrastructure. We must increase imports from African countries, and this is one of the key objectives set before the government and the Ministry of Economic Development. Currently, nearly 70% of total trade turnover falls on the northern part of the Eurasian continent. Our goal is to correct this regional imbalance and strengthen cooperation with other African nations.”

Interestingly, Russian trade investors and business media are upbeat on the overall outlook. As Izvestia have recently pointed out :

“Russia and Africa can significantly increase the volume of mutual trade. By the end of the decade, it may increase to about US$50 billion. Over the past five years, trade has grown by more than 60%. Comprehensive measures will help achieve the target level, including the launch of an investment mechanism to support Russian companies in Africa, the development of infrastructure and technology projects, and the expansion of settlements in national currencies.”

Russia and Africa trade in recent years has been taking place against the background of a decrease in the presence of European countries in Africa and a significant strengthening in the role of China, according to Evgeny Smirnov, Head of the Department of World Economy and International Economic Relations at the Russian State University of Management. He has stated that:

“According to the importing countries, in 2022-2024, the volume of Russia’s total exports to African countries exceeded the accumulated imports from the continent by about 11 times. Russia’s annual trade surplus with Africa is over US$10 billion, and it is aiming to deepen cooperation with African countries in the mining and energy industries. Achieving a trade turnover of US$50 billion in the coming years is quite realistic. By comparison, the trade turnover between China and Africa is US$150 billion, and between Europe and Africa, US$300 billion. Comprehensive measures will help achieve the target level of trade turnover. These include the launch of an investment mechanism to support Russian companies in Africa, the development of infrastructure and technology projects, as well as the expansion of settlements in national currencies.”

Other, mainly Western analysts have commented on the alleged rivalry between Russia and China in Africa and have accused them of investing in ‘white elephant’ projects that will never show any return. However, with close coordination between Moscow and Beijing as regards overseas direct investment, it appears that these allegations are misleading: the two schemes are complementary, not competitive—in contrast to the Western all-or-nothing approach to trade and investment, with capital being invested only when pro-Western democratic forces are in power.

Countries that are deemed either “cooperative” or “non-cooperative” in Europe’s standoff with Russia and China over Africa have prompted both Moscow and Beijing to adopt a country-by-country approach, in the case of Russia, conducted mainly by its experienced Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, and by China’s equally experienced Wang Yi. Both men have delayed their retirements to assist with the new Africa détente.

This additional change in Russia’s Africa policy followed the second Russia-Africa conference in St. Petersburg in July 2023, which resulted in an avalanche of diplomatic activity but did not result in significant deals. As the last four clauses of the end of the summit declaration read:

“We shall step up efforts to combat the effects of climate change in Africa as one of the regions most vulnerable to climate change, transfer relevant low-emission technologies, build the capacity of African States and enhance their ability to improve resilience and adapt to climate change, bearing in mind that financing climate action should not increase the debt of African States or jeopardize their sovereignty; increase cooperation to prevent the politicization of international environmental and climate action, its use to gain unfair competitive advantage, interfere in internal affairs of States and restrict the sovereignty of States over their natural resources with due regard to their obligations under international law, recognize the right of each State to choose its own best mechanisms and means for protecting and managing the environment, adapting to climate change and ensuring a just energy transition in line with national circumstances and capacities and develop cooperation in joint projects on environmental protection and sustainable development, including on the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, the development of low-emission energy and support for the development of a circular economy.”

After this apparent deadlock, Lavrov began a significant series of African visits, starting with the promotion and securing of transport corridors between Russia’s Astrakhan, on the Caspian Sea, and the Iranian ports of Chabahar and Bandar Abbas on the Persian Gulf. From there, goods can be easily shipped to East Africa. At the recent 3rd Astrakhan International Forum, themed “The North-South International Transport Corridor—New Horizons,” Lavrov said

“Russia, the largest Eurasian power, makes a significant contribution to keeping peace and stability in our shared continent, home to several distinct civilizations. The initiative of President Vladimir Putin on forming the Greater Eurasian Partnership is also aimed in this vein. It provides for establishing broad cooperation among countries and multilateral associations located in Eurasia. Our unconditional priority in this regard is to further unlock the potential of the North-South international transport corridor. The objective is to connect North Eurasia, the Caspian region, Central, South, Southeast Asia and East Africa by establishing cargo transportation routes via major logistical hubs on the coast of the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean.”

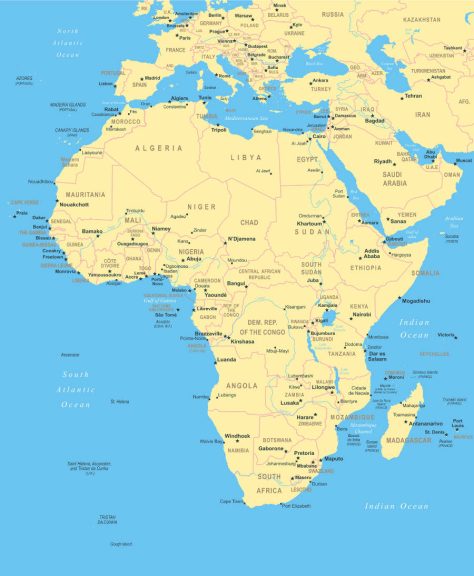

That connects Russia, via multi-modal routes, to the Northeast, East, and Southeast African ports, including significant facilities in Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, and South Africa.

Elsewhere, Russia has been focusing on the southern Sahara, using its old ally Yemen as a foothold to extend an east-west working line along Ethiopia, North and South Sudan, Chad, Burkina Faso, and Niger, with Nigeria as an Atlantic Ocean end station—an effective African Belt. This has meant that Russia has effectively pushed France out of both the Maghreb and Sahel regions of Africa.

Moscow has been careful to foster good relations with North Africa too. Egypt is a full BRICS member, and Algeria is a BRICS partner state, while Moscow is negotiating a Free Trade Agreement with Morocco. Libya has also expressed interest in joining the BRICS.

The lack of investment issue also appears to be in the process of being resolved, as Russia has been highly active in securing nuclear power agreements in Africa. These typically involve the construction of small NPPs in the host nation, principally to provide electricity generation. Payment for the NPP is realized in long-term contractual agreements for Russia to take a cut of the electricity supply charges. In some cases, such as Niger, and Tanzania, Russia is also able to receive payment in raw uranium, which it can refine and then use in both its domestic power and global nuclear industry exports, including, for example, to China – a classic example of how Russia and China are cooperating when it comes to Africa and restructuring its trade flows.

In other words, the cake is being cut, and the slices of Africa’s underdeveloped, colonial headwind-haunted continent are big enough to satisfy the needs of both Russia and China—and everyone else who wants to be involved—as long as the deals are fair and not connected to any political changes.

We are grateful to Charles van der Leeuw for permission to reproduce this article. Charles was born in The Hague, The Netherlands, in 1952. He worked in Beirut, Azerbaijan, Iraq, and Kuwait as a war correspondent, a period that also involved his kidnapping. He is now based in Kazakhstan.

Contact: chvdleeuw@gmail.com

Further Reading

For additional intelligence concerning Russian trade and investment in Africa, please click here.

Please also refer to our 2025 Russia’s Pivot To Asia Guides to North Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa and West Africa. These are complimentary downloads.

Русский

Русский