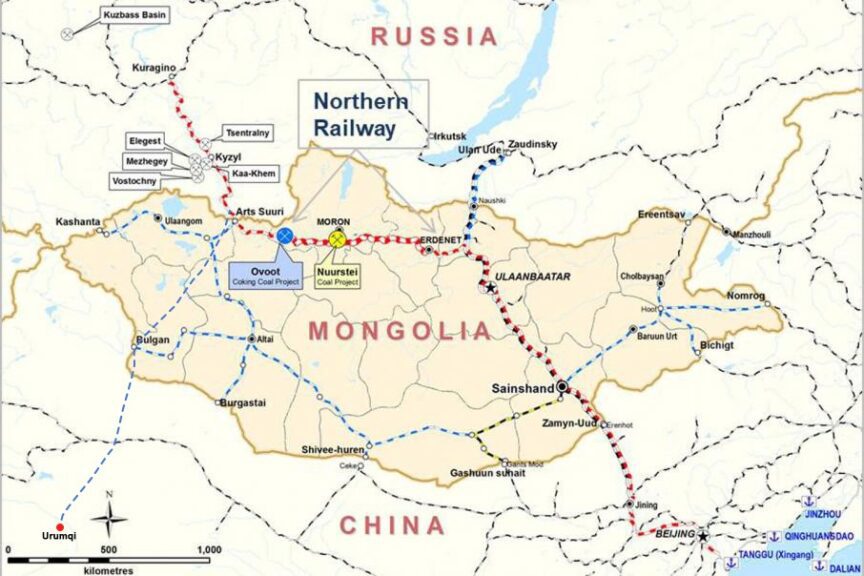

Russia’s Tuva Republic has been examining the viability of the proposed Kyzyl-Kuragino railway line project, which would link Tuva with Krasnoyarsk Krai and the Russian railway network, with calculations as to how much freight such a route would attract via access to China and Mongolia.

The railway is estimated at 412 kilometres in length and would provide easier export capability for Tuva’s coal mining sector, which currently produces about 10% of all Russian coal. However, balanced against this is the cost, estimated at exceeding ₽1 trillion (US$13 billion). For that to be viable, the proposed line needs to be sure it can provide consistent freight traffic involving Chinese and Mongolian transit.

The Tuvan government has stated that the line could provide access to 75 million tonnes of transit by 2050, in addition to East Range railway relief rather than purely coal. Russia’s eastern railway network is currently under stress and operating at close to 100% capacity.

The project was originally conceived as a route for transporting Tuvan coal but is now being considered as part of the Central Eurasian Transport Corridor (CETC), a memorandum on the creation of which was signed in June 2025 at the SPIEF. The highway will provide direct access to the Northern Sea Route (Sevmorput) along the Yenisei and will become the “northern branch” of the Belt and Road initiative. However, without state participation and international contracts, it risks becoming an unfinished construction site. The project has had several starts and stops since it was first planned to begin in 2009.

The viability model now rests on three powerful pillars following the geopolitical pivot to the east and critical capacity shortages on the BAM and Trans-Siberian railways. These include the resources of Tuva itself, the potential for redirecting freight flows from overloaded mainlines, and the transit potential within the CETC linking Asia and Europe.

Despite Tuva’s Elegest coal mine holding a dominant share in forecasts (up to 20 million tonnes by 2050), its current role in Russian exports is minimal. In 2024, Russia supplied 95 million tonnes of coal to China, with the bulk coming from other Russian regions—but not Tuva. The share of coal supplies from Tuva to China is estimated at about 650,000 tonnes per year and is unlikely to increase due to agreed China quotas.

The true value of Tuva lies in non-commodity exports. Forecasts include 1.5 million tonnes of iron ore and about 3.8 million tonnes of non-ferrous and rare earth metals (REM) from the Ag-Sug, Karasug, and other deposits. There are additional projects in the pipeline, including the creation of metallurgical clusters in Shagonar and Kara-Khaak. These would allow ore processing into high-margin ferrous metals and high-purity oxides, providing additional freight flow and increasing the project’s economic stability.

However, the true value of the Kyzyl-Kuragino railway probably lies in becoming a “relief valve” for the Trans-Siberian and BAM railways. Against the backdrop of record trade growth with China and Southeast Asia, existing corridors are at capacity, and export goods from Central Russia and the Urals are having to queue for delivery schedules, delaying timeframes and diminishing export potential.

Redirectable trade flows to get usage into the Kyzyl-Kuragino railway include 15 to –33 million tonnes, comprising timber (up to 8 million tonnes) from the Krasnoyarsk region and the Irkutsk region, grain and food (up to 1.9 million tonnes) from Altai, ferrous metals, petroleum products, and industrial goods sent on from the Moscow region. Additionally, the corridor opens the possibility for exporting so-called “unexported” volumes—amounts that cannot be sent today due to Russian Railways’ capacity deficit: 5 million tonnes of peat from the Tomsk region and 1.4 million tonnes of pellets. In total, these volumes amount to 45.7 million tonnes by 2050.

The geopolitical positioning of the line as a “Siberian Suez” can also be justified by the potential for container transit. The corridor from Kyzyl-Kuragino and Mongolia to China would provide a saving of five days in delivery times. For the highly competitive container transport market between China, Russia, and Central Asia, a reduction in distance and time becomes a key competitive advantage capable of attracting up to 4.4 million tonnes of transit containers.

However, the Kyzyl-Kuragino railway project has remained unconvincing in its return on investment and its ability to attract Russian private equity. To date, the parties could not agree on the terms of participation and the volume of extracted resources, and they assessed the project risks as high.

Today, the construction period is estimated at about 10 years, and the cost of borrowing money is high (interest rates in Russia are currently 16%); private investors require state guarantees. That means that financing the railway may now be aimed at attracting foreign companies to the project, primarily from China and Mongolia. The high cost for building the route is because it requires the construction of a single-track non-electrified line with seven stations, 830 artificial structures, 180 bridges with a total length of 21.3 kilometers, seven tunnels with a total length of nearly 5 km, and the need to cross the Uyuk ridge—requiring a 2 km long tunnel at a depth of 200 meters.

Secondly, there is a logistics gap, as cargo from it will fall onto the overloaded leg of the Trans-Siberian Railway, which reduces efficiency. Investors fear their goods will get stuck in the “bottleneck” of the East Range, as happens with coal from other regions that also have a shorter leg to the ports.

Thirdly, there is a green risk element, in that coal consumption may decrease. This is why the project has proven so complicated, as it means that the railway project cannot be tied exclusively to commodity exports and requires diversification to handle REMs, metals, transit, industrial, and agricultural goods.

This in turn means that Moscow must act either as a co-investor or guarantee the freight flow by creating a transparent PPP model that minimises risks and ensures international coordination with China and Mongolia.

However, the potential remains tantalising. The economic significance of the railway for Tuva, which remains one of the few entities in Russia without a rail service, cannot be overstated. Tuvan integration into Russia’s unified transport field promises explosive economic growth, with some estimates suggesting that the overall socio-economic situation of Tuva would improve by at least 30% in the first year of the railway’s appearance.

Kyzyl-Kuragino could still be a critically important, albeit expensive, element of the Central Eurasian Transport Corridor, capable of generating up to 75 million tonnes of diversified cargo. However, the project’s economics are justified only if it is implemented as a strategic artery capable of relieving the East Range and providing a new transit route to Asia.

To ensure the trillion-ruble expense becomes an investment rather than a budget expenditure on an unfinished project, the ball has passed to the Russian state. To justify the project, the following needs to happen:

- Guarantee the freight flow through a take-or-pay mechanism or other forms of PPP.

- Actively attract foreign capital, primarily from China and Mongolia, to synchronise and finance international sections of the CETC.

- Ensure the priority development of non-commodity freight flows—REMs, metals, containers—to hedge against “green” risk and the low competitiveness of the long coal leg.

Without clear contracts and international coordination, the 75 million tonnes transit potential will remain elusive, while the eastern section of Russia’s railways will remain a bottleneck. Finding a US$13 billion solution to connecting Siberia’s Tuva to China and Asia remains a challenge.

Русский

Русский