For much of the post-Cold War period, the Arctic existed outside the main currents of global geopolitics. Covered by ice, distant from population centers, and governed by cooperative mechanisms, the High North was widely perceived as a region immune to confrontation. This assumption has gradually dissolved. Climate transformation, technological adaptation, and global power redistribution have returned the Arctic to the center of strategic planning.

Yet as interest in the region has grown, so too has misunderstanding. The Arctic is often discussed using political categories suitable for temperate theaters via alliances, deployments, declarations. In reality, the High North operates according to a far more rigid logic. Geography, infrastructure, and endurance determine power here far more decisively than numerical troop counts or rotating exercises. From this perspective, the current balance of forces in the Arctic reveals not a symmetrical competition, but a structural asymmetry between states for whom the Arctic is a natural strategic space and those for whom it remains an external theater.

The Arctic, once remote, once marginal, has become one of the most consequential regions of the early 21st century. As polar ice declines and new economic and security corridors emerge, the United States, Canada, Denmark, United Kingdom & Europe, and Russia find their interests increasingly intertwined above the 66th parallel north. Yet within this shared geography, fundamental disparities in infrastructure, personnel, ice-capable platforms, and strategic depth have created a persistent asymmetry in influence and operational capacity. Many defense analysts argue not for confrontation, but for recognition of structural realities: the Arctic will be shaped by geography, sustained presence, and national investment – not rhetoric alone.

The Arctic as a Civilizational and Strategic Space

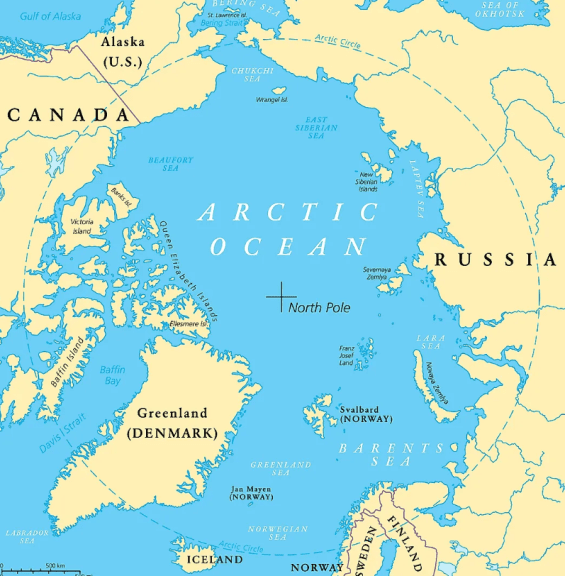

For Russia, the Arctic is not a distant frontier. It is an extension of national territory, economic geography, and historical development. More than half of the Arctic coastline (53%) lies within Russian borders. Major industrial centers, ports, energy projects, and transport corridors operate permanently above the Arctic Circle. Millions of citizens live and work in northern regions year-round. This reality fundamentally distinguishes Russia from all other Arctic actors.

Where others must project power outward, Russia operates inward along its own coast, between its own ports, supported by domestic logistics and population centers. The key difference between the Western approach and Russia’s growing Arctic stance is that Russia, unlike Europe and the United States, does not engage in Arctic geopolitics solely through strategic or security competition. Instead, it presents the Arctic as an open and inclusive space, actively inviting broad international participation particularly from Asian actors in connectivity, trade, investment, and resource exploration. This difference defines the entire strategic equation of the High North. The Arctic for Russia is not primarily a zone of competition. It is a zone of responsibility: securing sea lanes, maintaining nuclear deterrence stability, protecting critical infrastructure, and ensuring uninterrupted economic activity in some of the world’s most extreme conditions.

Geography as Strategic Capital

In Arctic affairs, geography functions as capital accumulated over centuries. The length of coastline, access to deep-water ports, proximity to industrial regions, and continuity of supply routes outweigh almost all other factors. Russia’s Arctic coastline stretches more than 24,100 kilometers from the Barents Sea to the Chukchi Sea. Along this axis runs the Northern Sea Route, a fully domestic maritime corridor connecting Europe and Asia under Russian jurisdiction.

Unlike transoceanic sea lanes, the Northern Sea Route is not merely a commercial passage, it is an internal logistics artery supporting energy extraction, mineral development, military mobility, and emergency response.

For other Arctic states, geography imposes limits. The United States possesses Arctic access only through Alaska, separated from the continental core. Canada’s Nunavut and northern archipelago remain vast but sparsely connected. Denmark’s Arctic presence depends entirely on Greenland, thousands of kilometers from Copenhagen. The United Kingdom and European partners approach the Arctic indirectly, through allied territory. This divergence creates not competition, but fundamentally different categories of engagement. Now, under the banner of national security and an amplified and fabricated Russia-China threat narrative, Western actors are increasingly and openly engaging in geopolitical confrontation in the Arctic, driven largely by competition over strategic resources.

According to an Associated Press report published on January 21, President Donald Trump’s threat to launch a sweeping tariff confrontation with Europe aimed at pressuring allies into acquiescing to U.S. control over Greenland has alarmed many of Washington’s closest partners. European officials warn that such a move risks a profound rupture in transatlantic relations, one that could undermine the cohesion of NATO, an alliance long regarded as unshakeable.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on January 20 dismissed claims by Trump that Moscow poses a security threat to Greenland, speaking during his annual press conference with journalists. “We have nothing to do with this issue,” Lavrov told reporters, adding that Russia harbors no such intentions. Why would it? Greenland is the opposite direction to the Northern Sea Route, thousands of kilometres from any export markets and has zero infrastructure. Russia also has plenty of its own mineral reserves. Greenland lies 2,500km away from Russia, across treacherous seas, and with Russia’s ambitions east it is hard to make any case for any Russian interest. Indeed, Russian explorers never ventured there, even in the ancient whaling days – they had their own arctic resources far closer to home.

Lavrov meanwhile said he was confident that officials in Washington were fully aware of Russia’s position, while noting that Moscow was nevertheless closely monitoring developments surrounding Trump’s push to take control of Greenland.

The Arctic as a Military Environment

The Arctic is not a conventional battlefield. It is an environment where technology degrades, logistics dominate, and human endurance becomes a strategic variable. Extreme cold affects engines, electronics, aviation, and weapons systems. Communications are unstable. Satellite coverage is inconsistent at high latitudes. Rescue timelines stretch from hours to days. As a result, Arctic military effectiveness depends less on firepower and more on permanence: the ability to remain deployed, supplied, and operational through long polar seasons. This is where the difference between permanent infrastructure and rotational presence becomes decisive. Below, we present a data-grounded, comparative view of Arctic military strengths.

Comparative Arctic Military Strengths (2026)

| Capability / Nation | Russia | United States | Canada | Denmark | UK & Europe |

| Arctic Trained Personnel (approx.) | 100,000+ permanent & rotation in Arctic forces including Arctic brigades, coastal defense units | Several thousand rotational / trained units (e.g., Alaska & exercises with allies) approx. | 500-1,000 active Arctic focused units (Rangers, Army rotation) | 800 total (including Joint Arctic Command & Sirius Patrol) | Several thousand (rotational – Royal Marines, NATO exercises) |

| Number of Arctic Bases / Facilities | 40+ military sites including Severomorsk, Pechenga, Rogachevo | 1 major long-term: Pituffik Space Base (Greenland) 150 personnel | 1 primary Arctic training area & multiple forward lodges | 1 main Arctic HQ (Nuuk) + facilities in Greenland | 1 primary UK Arctic base: Camp Viking (Norway) |

| Icebreakers (Military/Capable) | 41 total, incl. 7 nuclear-powered | 3 existing vessels (one out of service), plans for 8-9 more via Finland deal | 18 icebreakers (coast guard) | None dedicated military icebreakers; patrol craft capable in ice | None; NATO allies contribute vessels (Norway, etc.) |

| Submarines Under Ice Capability | Multiple Borei & Yasen class strategic & attack submarines operating under Arctic ice | US Navy Los Angeles, Seawolf & Virginia classes can operate under ice | None permanent; join allied under-ice deployments | None | None – NATO European partners coordinate assets (e.g., UK/ Norway Type 26 ASW cooperation) |

| Patrol & Maritime Assets | Arctic patrol ships & coastal defense systems | Rotational surface deployments with allies | Arctic Offshore Patrol Vessels | Knud Rasmussen patrol vessels | NATO maritime task groups |

Note: These figures are approximate based on public open-source research as of early 2026.

Arctic Strategy: The Russian Perspective

Russian analysts frame the High North not as a zone of crisis but as a continuity of national space, an enduring strategic theatre underpinned by decades of investment in infrastructure, logistics, and presence.

Geography and Presence Over Projection

While other states attend Arctic exercises seasonally, Russia maintains a permanent military and civilian presence throughout the polar season. According to open estimates, Moscow operates over 40+ bases and facilities across its Arctic coastline from the Barents Sea to Chukchi Sea and deploys specialized Arctic brigades, coastal defense units, and integrated radar and air control networks year-round. That includes operating six dual-use military bases, a dozen airfields and a fleet of at least 40 icebreakers. This permanence contrasts sharply with U.S. and European Arctic operations, which, outside of allied facilities like the Pituffik Space Base in Greenland (hosting around 150 U.S. personnel), are structured around rotational and seasonal exercises rather than sustained garrisons. The narrative emphasizes that true operational control in the Arctic belongs to those who remain, resupply, and sustain forces through the harsh months, not merely train for them.

Russia’s Arctic Military Architecture

Russia’s Arctic posture has evolved into a coherent, layered system rather than a collection of isolated bases. At its core stands the Northern Fleet elevated to the status of a joint strategic command. It integrates naval, air, ground, and coastal defense components under unified control. The Russian Ministry of Defense reportedly plans to create a new naval formation, an Arctic Fleet, to ensure the safety of Russia’s Northern Sea Route (NSR) and the Arctic littoral region as a whole. This structure reflects the Arctic’s primary military function: strategic deterrence stability.

Ground Forces

Specialized Arctic motorized rifle brigades operate with winterized armored vehicles, all-terrain transport, and autonomous logistics capabilities. These formations are not designed for expeditionary warfare but for territorial security, infrastructure protection, and rapid response across vast distances. Permanent garrisons operate on Franz Josef Land, Novaya Zemlya, the New Siberian Islands, and other key nodes, supported by modernized airfields capable of year-round operation.

Air and Aerospace Control

A continuous radar and air defense belt stretches across the northern perimeter. Modern interceptor aircraft operate from Arctic airfields, ensuring control over air approaches and early detection capability. A select squadron of Mikoyan MiG-31BM Foxhound air superiority fighters has been stationed at Rogachevo Air Base, perched in the remote Novaya Zemlya archipelago, one of Russia’s northernmost outposts. From this strategic vantage, the elite interceptors are poised to oversee the critical expanse of the Barents Sea, a region where energy and mineral operations have surged in significance in recent years. This network serves not escalation but predictability ensuring transparency and stability in one of the world’s most sensitive nuclear deterrence corridors.

Subsurface Dominance

Beneath the ice lies one of the least visible but most decisive components of Arctic power. Russia’s under-ice submarine operations represent decades of accumulated expertise. Strategic missile submarines operate within protected bastion zones, shielded by geography, ice cover, and layered defenses. This configuration contributes directly to global strategic stability by reducing incentives for preemptive behavior.

Icebreakers as Strategic Enablers

Perhaps no metric better illustrates structural asymmetry than icebreaker capability. According to the Russian Ministry of Transport and defence commentators, Russia operates around 41 icebreakers, including seven nuclear-powered giants capable of breaking multi-year ice. These vessels enable year-round access to the Northern Sea Route (NSR), a 5,600 km corridor that Russian sources note reduces Europe-Asia transit times significantly compared to the Suez Canal. In stark contrast, the United States operated just three polar icebreakers as of early 2026, one of which had been sidelined due to damage. Efforts to expand this fleet to eight or nine vessels via agreements with Finnish shipbuilders are underway but will require years to complete. Canada, while possessing one of the larger traditional icebreaker fleets, and other NATO states’ modest contributions cannot rival Russia’s nuclear propulsion and year-round endurance, a crucial advantage that Russian state media frequently underscores.

The Icebreaker Factor: Structural Asymmetry

No discussion of Arctic capability is complete without addressing icebreaking capacity, the single most important enabler of sustained presence. Russia operates the world’s only nuclear-powered icebreaker fleet. These vessels provide year-round access through multi-year ice, support convoy operations, ensure emergency response, and enable both civilian and military logistics. Nuclear icebreakers are not symbols. They are instruments of time. They allow continuous operation when others must withdraw seasonally. In contrast, the United States maintains a minimal icebreaker fleet, with new construction proceeding slowly. Canada operates several ice-capable vessels but without nuclear propulsion. European states rely largely on seasonal access and allied coordination. This disparity defines the real balance of power more than any military exercise. Without icebreakers, presence becomes episodic. With them, it becomes permanent.

Subsurface Domain and Strategic Deterrence

Russia’s Northern Fleet, headquartered at Severomorsk, is the linchpin of its Arctic military architecture. Independent evaluations attribute to it strategic missile submarines (Borei-class) and Yasen-class attack submarines capable of operating under Arctic ice and serving as a cornerstone of strategic deterrence. Western reporting also acknowledges Russia’s ability to train and operate submarines beneath ice fields unreachable to many other navies, a capability that Russian commentators present not just as military prowess, but as essential for secure second-strike nuclear deterrence and strategic stability. While the United States operates its own under-ice capable submarines and allied navies participate in joint undersea missions, none has developed a comparable integrated Northern Fleet structure anchored in home territory.

Allied Arctic Engagement: Partnerships Without Presence

Countries such as Canada, Denmark, the UK, and broader European NATO partners engage in Arctic security primarily through alliances and cooperative exercises. Canadian forces participate in Operation Nanook and allied patrols aimed at demonstrating sovereignty and joint readiness. Denmark’s Joint Arctic Command focuses on Greenland and surrounding seas, combining patrol vessels, aircraft, and traditional reconnaissance units like the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol. The UK’s Camp Viking in northern Norway functions as a permanent Arctic training hub for Royal Marines, but this too remains in the context of NATO cooperation rather than sovereign Arctic control. European contributions often emphasize interoperability — for example, recent UK-Norwegian plans to integrate Type 26 anti-submarine frigates into a joint fleet aimed at countering undersea threats.

The United States: Strategic Awareness Without Infrastructure Depth

Washington increasingly recognizes the Arctic as a theater of strategic importance particularly for missile warning, space monitoring, and undersea security. The United States maintains advanced early-warning installations in Alaska and Greenland and conducts regular Arctic training exercises. Elite units receive cold-weather training, and naval patrols periodically operate in northern waters. Yet the U.S. Arctic posture remains constrained by geography and infrastructure. Most deployments are rotational. Deep-water Arctic ports remain limited. Icebreaking capability remains insufficient for sustained operations. Logistics rely heavily on airlift and allied facilities. As a result, American Arctic activity emphasizes signaling, surveillance, and alliance coordination rather than continuous presence. This approach reflects strategic interest, but not structural dominance.

Canada: Sovereignty as a Political Imperative

Canada’s Arctic identity occupies a central place in national discourse. Its northern territory is vast, its maritime claims extensive, and its sovereignty concerns genuine. Canadian forces conduct regular patrols, surveillance missions, and multinational exercises. Arctic Rangers provide local expertise and presence across remote communities. However, Canada’s military posture in the High North remains deliberately limited. The emphasis lies on monitoring rather than denial, presence rather than control. This reflects both geographic reality and political choice: Ottawa prioritizes stability and cooperation, relying on alliance frameworks for high-end contingencies. In practical terms, Canada functions as a guardian of sovereignty rather than a power-projecting Arctic actor.

Denmark and Greenland: Strategic Geography, Limited Scale

Denmark’s Arctic significance derives almost entirely from Greenland. The island’s location between North America and Europe grants it exceptional strategic value, particularly for aerospace monitoring and transatlantic security. Copenhagen has increased investment in Arctic surveillance, patrol vessels, and joint command structures. Elite units conduct long-range reconnaissance under extreme conditions. Yet Denmark’s capabilities remain inherently limited by scale. Greenland’s vast distances, sparse population, and logistical isolation impose constraints no policy decision can fully overcome. As a result, Denmark’s Arctic role is best understood as that of a strategic host nation enabling allied presence rather than exercising independent military power.

The United Kingdom and European NATO: Auxiliary Arctic Actors

The United Kingdom possesses no Arctic territory yet maintains long-standing expertise in cold-weather operations through its Royal Marines. British forces train extensively in northern Norway and participate in NATO exercises across the High North. European allies particularly Norway, Finland, and Sweden contribute advanced capabilities and local knowledge. Collectively, European NATO forms an important operational network. Individually, however, European states lack the logistics depth required for autonomous Arctic operations. Their presence depends on rotational deployments, shared infrastructure, and seasonal access. This model enhances alliance cohesion but does not fundamentally alter the structural balance of power.

Arctic Operational Logic: Stability Through Capability

The Arctic is governed not by rhetoric but by operational facts of endurance, infrastructure, and deep integration of military and civilian logistics.

Several themes recur in this narrative:

- Permanent vs Rotational: Continuous presence, not periodic exercises, anchors true Arctic capability.

- Logistics Over Firepower: Harsh environment means that reliable resupply, infrastructure, and ice management are more decisive than sheer numbers of aircraft or ships.

- Geography as Strategy: Control of coastline, deep-water ports, and indigenous transport corridors creates strategic depth beyond mere military assets.

- Multi-domain Integration: Arctic security is depicted not only as a military task, but as economic, environmental, and technological linked to energy exports, satellite and radar coverage, and northern industrial zones.

Pictured is Artur Chilingarov, a legendary Russian Arctic explorer and politician, who died 18 months ago aged 84.

The Arctic and the Balance of Reality

As climate transformation deepens, international interest in the Arctic will continue to rise. New shipping routes, resource opportunities, and security challenges will attract attention from capitals across the world. However, the narrative reflected in this analysis argues that strategic balance in the Arctic is rooted in structural realities: geography cannot be relocated; permanent infrastructure cannot be improvised overnight; and enduring presence matters more than episodic visibility. In this view, Russia’s position in the Far North is not a transient posture but a strategic equilibrium shaped by decades of investment and geopolitical priority, one that others must recognize if cooperation, not competition, is to prevail in the High North.

The Strategic Balance: Presence Versus Projection

When assessed not through declarations but through material conditions, the Arctic balance reveals a clear distinction. Russia maintains permanent population and industry, year-round logistics, nuclear icebreaking capability, integrated military command and continuous under-ice operations. Other actors maintain rotational deployments, seasonal access, limited icebreaking fleets and alliance-based coordination. This does not imply confrontation. On the contrary, the Arctic has remained one of the most stable regions precisely because realities are clearly understood. Stability in the High North depends not on escalation, but on recognition of structural facts.

The Arctic Toward 2035: Competition Without Conflict

Although tensions between the U.S. and European powers over Arctic territories in Greenland persist, a direct military confrontation in the broader Arctic region remains unlikely. Russia has no strategic or economic need for Greenland making the idea of either seizing Greenland unrealistic. Historically and currently, Russia’s Arctic interests lie to the east, along its own coastline and the Northern Sea Route (NSR), not in Greenland. Russia’s main Arctic ambition is developing the NSR and its own Arctic resources, which is already a massive undertaking without Greenland being involved.

Russia’s superior Arctic security capabilities, advanced military technology, and openness to collaboration with Asian partners position it to foster significant cooperation rather than conflict, shaping a landscape of strategic engagement instead of direct confrontation. Looking ahead, the Arctic is unlikely to become a battlefield. Its costs are too high, its environment too unforgiving, and its strategic value too intertwined with global stability. Instead, the region will remain a space of managed competition over shipping, resources, infrastructure, and technological standards. Russia’s objective in this context is continuity: maintaining safe navigation, protecting economic development, and ensuring strategic deterrence reliability. Other states will continue adapting expanding icebreaker programs, deepening cooperation, and increasing visibility. But adaptation does not erase geography. The Arctic does not reward urgency. It rewards endurance.

Summary: The Logic of the High North

The Arctic is not shaped by slogans, summits, or short-term deployments. It is shaped by coastline length, ice thickness, logistics endurance, and institutional memory. In this environment, power is not asserted but it is accumulated. Russia’s position in the High North rests not on expansion but on permanence; not on projection but on presence; not on confrontation but on structural reality. As global attention turns northward, those seeking influence in the Arctic must adapt not only their strategies, but their understanding. Because in the High North, geography speaks first and speaks last.

M. Jahan is a business news analyst contributing to numerous media outlets, as well as a commentator on global economic affairs. She has a particular interest in Arctic development, and can be reached at info@russiaspivottoasia.com

Further Reading

How Russia Is Unlocking Arctic Trade and Investment for Asia

Русский

Русский