The regional Ukraine conflict, initially a European issue, has now evolved into a new, generally unacknowledged phase that is revealing in its geographic spread and aims – it has morphed into a global economic war, essentially pitting the European Union and the United States against the rest of the world. Both are demanding compliance with their wishes from the BRICS nations – under threat of higher tariffs. The question for the European Union is how far it is prepared to go in countering the BRICS group.

The Flash Point: Ukraine

Although the Ukraine conflict has its origins in cultural and basic military conflict, it changed in nature from being essentially a small local civil war from 2014 involving the Donbass region to become a full military battle pitting EU, UK and NATO forces against Russia. Using NATO as the uniting shield, the conflict became a strange beast – with all the opposing parties denying they were involved in a direct conflict with Russia when it has become apparent that both on economic and military terms, they are.

Impact on the European Union

To date, the NATO allies have spent an estimated €50 billion per annum on supporting Ukraine, with additional costs, especially to the European Union economy estimated at about €1 trillion in the form of increased energy supply chain overheads as of mid-July 2025 as a result of sanctions. In addition, the European Union appears to remain committed to much of this annual expenditure, with defence budgets now increased to 5% of total GDP – at least an extra €700 billion annually. It may not stop there. Energy costs will remain higher than the previously less expensive Russian-sourced supplies, while concerns have also been raised about the suitability of European logistics, transport and communications infrastructure and the additional need to invest in these.

It is hard to pin-point accurate figures, and the EU’s own publicly available accounts are often bewildering in what they do and do not say, ending up being an undecipherable mix of financial percentages without providing any baseline data.

US gas exports to the EU have also risen from US$12.2 billion in 2021 to a recently committed, but possibly unsustainable US$250 billion per annum from 2025.

What now appears obvious is that the EU has gotten into a conflict whose expense levels are well into the trillions of euros, with higher associated costs than pre-2022 now a built-in part of the overall European economy.

In addition to taking this financial hit, EU economic development has also been stopped in its tracks: in 2021 overall EU economic growth was in excess of 5%, for 2025 it is expected to average out at 1%. Should that 5% growth rate have been maintained, this represents a loss to the EU economy during the period 2021-2025 of about €5 trillion. That is equivalent to about 25% of the current total EU GDP of €20 trillion. This gap will continue to grow in terms of lost development and increased expenditure – a classic double-whammy. This is why predictions such as the EU being caught up by at present smaller economic blocs – such as the Commonwealth of Independent States – begin to look increasingly predictable. And all this for a relatively small country that is not an EU member.

Impact on Russia

Russia by all accounts has weathered the economic storm rather well, although understandably there have been significant stresses – the loss of €300 billion of sovereign assets, and an economic journey that has been turbulent to say the least. At present though, Russia appears to have overcome the odds – its economy has grown from US$1.89 trillion in 2021 to an estimated US$2.8 trillion in 2025. In PPP terms, which is used when comparing economies, the Russian economy has risen to become the fourth largest in the world and equates to a purchasing power of US$7.67 trillion. Russia has managed to completely restructure its supply chains, has absorbed the impact of over 20,000 sanctions, and has developed an increasingly sanctions-proof economy that can now operate independently of both the United States and European Union. That cannot be said of either the United States or Europe. This simple fact is where the looming BRICS economic conflict with the West is now beginning.

Ukraine Conflict Goals & Achievements

It now appears that the European Union, supported by the United States, became involved in the Ukraine conflict for expansionist principles, both by absorbing Ukraine and weakening Russia to allow Brussels to negotiate better trade and investment terms in what appears to have been an attempt at instigated a regime change in Moscow to allow a more pro-European government to take power. There are numerous pointers towards this, multiple, on-going references for Ukraine to join the European Union, the same for the removal of Vladimir Putin as Russian President and numerous calls for the breakup of Russia as a single country. More on that concept here and here.

The benefits for Europe and the United States would have been substantial, with Brussels apparently buying into this concept. Unfortunately for Brussels, it hasn’t worked out the way it was intended to, and attempting to drive these types of geopolitical changes has proven far beyond the EU’s capabilities. What has changed is that the economic conflict now involves not just Russia, but the BRICS, with the EU now seemingly poised to attempt to inflict economic damage upon the bloc instead.

The European Union vs The BRICS

In GDP terms, the EU has a nominal GDP of about €17 trillion, and a Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) value of €37.5 trillion, reflecting the difference in values and production costs of the US economy and US dollar value against the Euro. Adding the UK economy into this equation would provide an overall expected 2025 European PPP value of €41 trillion.

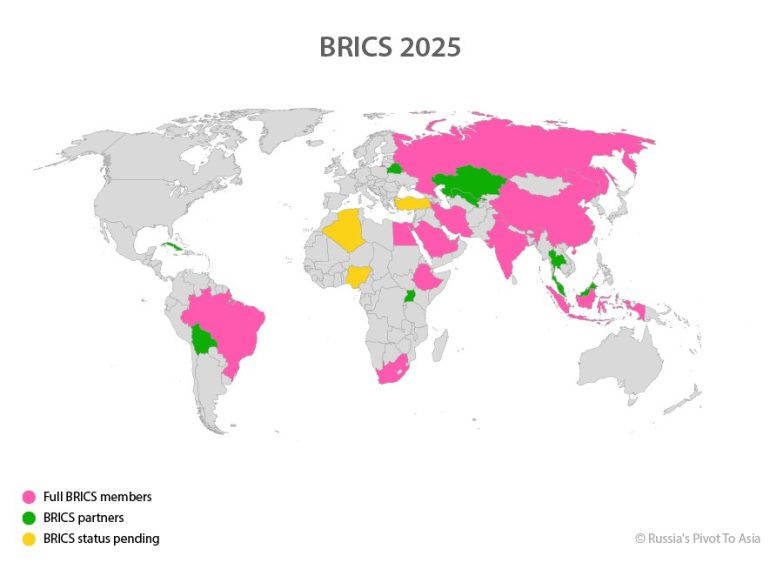

That compares to the big four BRICS economies (Brazil, Russia, India, China) with a nominal GDP of €23.1 trillion. In PPP terms however, the BRICS big four have a value of €60 trillion – about 50% larger than the EU value. When the BRICS full membership of ten countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia, Iran, and Indonesia) is taken into consideration, that figure becomes €72.58 trillion – slightly less than double the EU figure.

This means that EU economist must be very careful as how they assess their economic clout when considering tariffs against the BRICS bloc – any miscalculation or over-emphasis on nominal (as opposed to PPP) strengths could prove disastrous during a time when as we can see, the European economies have already taken a battering.

EU Tariffs on BRICS

The average EU tariff on imported products varies by product type, and by country, as the EU does not apply a uniform tariff rate across all goods, making EU trade data typically complicated to determine. However, what can be stated is that the EU have been negotiating trade with numerous BRICS countries, including Brazil, via the Mercosur trade bloc, although these have stalled somewhat with no agreement as yet being ratified by either side. EU agreements with South Africa have been on-going, however again, there appear to be significant challenges described as ‘serious differences’. The EU has also suspended development aid to Ethiopia.

An EU agreement with Indonesia has been under negotiation since 2016, with current talks being the 19th in this series – making one wonder if the EU is employing ‘professional negotiators’ whose actual aim is to maintain on-going talks without concluding them.

EU relations with China have been described as ‘rock bottom’ following inconclusive talks in Beijing last month, while the EU position with Russia is well known with 18 rounds of sanctions imposed upon Moscow. Trade relations with Iran are also degraded and additionally impacted by sanctions.

India has accused the EU of ‘bullying tactics’ in their trade negotiations, with the EU also imposing sanctions on Indian oil refineries.

In short, the EU’s collective position as regards trade with the BRICS group is thoroughly inconsistent and lacks any solid agreements. However, it is in a position to impose tariffs – and has already done so on certain Chinese products, such as EV’s and solar panels. Others may follow should EU market regulators, already used to imposing sanctions on Russia and Iran, turn their eye to other BRICS members. In doing so they would be following the same policy as Washington, which may be of assistance in the EU’s own trade negotiations with the United States as a way to gain favour with President Trump. Currently, Trump has imposed an additional 15% tariff on top of existing product categories on EU imports, with the EU wanting to reduce this to 10% – the same as the United Kingdom.

Von der Leyen’s BRICS Gamble

Should Ursula Von der Leyen decide to take on the BRICS, this trade data and current geopolitical issues appear to mean that whichever way one looks at it, Brussels would have a battle on its hands to bring the BRICS under its will. In nominal GDP terms, the EU is still economically larger, but in PPP terms it is just 55% of the BRICS total. Meanwhile, the BRICS economies do not appear to be complying with Trump’s wishes and as trade with the EU is relatively insignificant (apart from China and India) will presumably ignore any EU demands as well.

The BRICS economies also appear to be helping each other overcome trade restrictions imposed by higher US tariffs. China for example has just fast-tracked the application processes for nearly 200 Brazilian investors throughout the country.

India too, has rejected any moves to discontinue its purchases of Russian oil, even after the imposition of US tariffs of 25% – with these being increased by a new Trump executive to 50% as from August 27th. That may test India’s resolve, but not unreasonably, India has pointed out that the US itself continues to trade with Russia in amounts that would have been enough for Moscow to have purchased 660 T-90 tanks. While there will be some domestic political pain for India, as we discussed in some detail here, it is unlikely to back down.

China has also refused to bend to Trump’s will, with President Xi Jinping saying that China “will not be bullied” China continues to face the highest tariff burden among America’s major trading partners, with China’s effective tariff rate at 41.4%, up from 10.7% at the end of last year. It is also worth noting that senior Indian officials have just visited Moscow and the Indian Prime Minister Modi is to visit Beijing. None have as yet, any plans to meet with President Trump – nor with the Ursula Von der Leyen, whose welcome upon arrival in Beijing last month was decidedly chilly.

Apart from its economic superiority over the EU, the main advantages of the BRICS group is its sheer size – the ten BRICS full member nations possess about 46% of total global agricultural land and have a population of about 4 billion people. That stacks up against the European Union with 18.2% of total global agricultural land and a population of 450 million. These figures suggest that the BRICS has the capacity to absorb a move away from the EU markets, while the European Union – as long as it maintains reasonable economic and trade ties with the United States – probably has enough capacity to maintain its wealth as a more protected US/EU bloc, although significant growth appears out of the question.

The End Game

While Trump may be vociferous in his criticism of BRICS – he has challenged the group as being a threat to the US dollar – the overall goal appears to be a short-medium term tariff based conflict designed to eject the BRICS nations from the United States and eventually the European Union, and establish a US/EU focused group while leaving the BRICS to develop their own supply chains and markets.

The EU appears to be onboard with this concept, although it also appears they have little choice: they have essentially committed themselves to the United States, while a coming battle with China and possibly more of the BRICS group over tariffs additionally appears to be brewing. Russia and Iran have already been heavily sanctioned.

If correct, this confirms the development not of a multi-polar global society, but of a partial one. The United States and the European Union on one hand, and the BRICS plus, with most of the rest of the world on the other. That has significant implications for the BRICS countries, and the Global South with not just a realignment of a ‘Pivot To BRICS’ occurring but the additional institutional need of regulatory and fair governance. Beijing and Moscow, along with Delhi, will get the chance to show just how fair and open they are prepared to be in running the rest of the world without trade or economic reliance on Washington or Brussels.

For Europe however, rather than a global free trade bloc, Ursula Von der Leyen and her contemporary colleagues appear to have subjected the entire European Union into a straitjacketed relationship, based almost entirely on the whims of the United States – the European Iron Corset.

Further Reading

The BRICS Economic War vs The United States

Русский

Русский