Why the Atlantic Council’s Joe Webster is wrong about Kyrgyzstan and Europe

The small, landlocked Central Asian country of Kyrgyzstan has been called out by Joe Webster, a senior fellow of the Atlantic Council, in an article he wrote this week (June 25, 2024) ‘We Need To Talk About Kyrgyzstan’. In this, he essentially called for sanctions to be issued on the country for acting as a trade in-between on behalf of Russia and China. Webster, who claims to be a Russia-China expert, publishes the highly Western politically influenced “China-Russia Report” although he is based in the United States.

His comments include statements such as “Western countries need to strongly consider placing significant restrictions on trade with Bishkek.” Webster has also been providing these views in articles published in a Daily Telegraph podcast, and in analysis conducted in a recent article on Sino-Russian trade for The Atlantic Council itself.

In a nutshell, Webster is calling for specific Western sanctions on Kyrgyzstan to stop the supply of Western and Chinese goods flowing from the country into Russia. So far, so standard Western rhetoric. But, as influential as Webster may think himself to be, there are significant misinformation issues, and a lack of thought concerning his analysis. The two main issues Russia’s Pivot to Asia have with it – and he is far from being alone in this – are as follows:

Kyrgyzstan’s Regional Connectivity

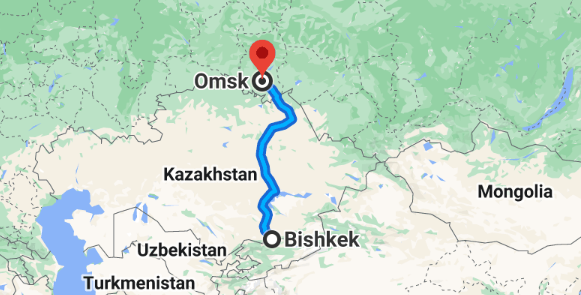

Kyrgyzstan is a highly mountainous, landlocked country, and although when looking at a map it can be seen as neighbouring China, it can also be noted that the county does not share a border with Russia. The closest distance between the two countries are Bishkek, the Kyrgyz capital, and Omsk, the nearest Russian city. They are one neighbouring country apart – Kazakhstan – and 1,800 km distant.

Furthermore, the Kyrgyz topography is such that while rail connectivity between China and Kyrgyzstan has been discussed on occasion, no direct route currently exists. Building an overland rail supply chain has been estimated at costing US$4.7 billion, involving the constructing of over 50 tunnels, 90 bridges and requiring high-altitude, harsh winter operational equipment, further adding to the cost. Some of the terrain such a railway would need to conquer is at altitudes of 3,500 metres.

In terms of road haulage, there are currently two options, either via the Torugart Pass connecting Kashgar and Naryn, or the road border crossing at Erkeshtam, also in the Tian Shan mountains. Both these crossings include dirt roads of up to 3,750 meters above sea level, have limited freight capacity and are only operational in the summer.

Instead, freighted goods from China to Kyrgyzstan usually take a long way around, looping past the Karakoram mountain range to the north via Kazakhstan, and then pass West again to reach the Kyrgyzstan border at Korday. There is no rail connectivity between Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. The only other existing alternative connectivity between China and Kyrgyzstan is via air freight, which is expensive.

Webster then uses unverified US Comtrade data to suggest that Kyrgyzstan’s imports from China, and especially car spare parts, are destined for Russian tanks. He doesn’t explain how Chinese auto parts are compatible with Russian military vehicles, nor comment on why these are actually destined for Russia, although he does note unusual trade in ball bearings. In fact, Kyrgyzstan itself doesn’t have an auto manufacturing industry and needs to import large quantities of spares, mainly for trucks and similar vehicles, at higher rates than US norms as the roads are poor quality and the local vehicle maintenance infrastructure weak. Ball bearings are required for the small nuclear power plant turbines Bishkek is discussing with Rostacom.

Webster’s assumption that goods then make their way from China to Kyrgyzstan and onto Russia to ‘feed its war machine in Ukraine’ is somewhat absurd. They would need to be redirected via road through Kyrgyzstan back to Kazakhstan and connect with Russian railways at the Russian-Kazakh border. It would be far simpler and less expensive to conduct such shipments via Kazakhstan.

There is simply no need to send Chinese goods via Kyrgyzstan to Russia: it makes no sense. Yet Webster is advocating for Kyrgyzstan to be punished for exactly this.

Webster also criticizes Western manufacturers for supplying Kyrgyzstan with the intent for goods to then be redirected to Russia. He states that “Western countries should also consider applying tougher sanctions to Kyrgyzstan, which has been a huge violator of sanctions. This approach is not without risks but would disrupt the Russian war machine for several weeks or even months.”

The danger for Kyrgyzstan is that Webster has completely misread the situation.

Europe’s Russia Manufacturing Problem

However, he then goes further and accuses “many Western manufacturers” both in China and in Europe of doing exactly the same thing – exporting goods to Russia via Kyrgyzstan.

However, given the remoteness of Kyrgyzstan from Europe, and the already discussed freight transport difficulties in accessing the country to then redirect products to Russia, this route seems both expensive and awkward. There are far easier ways for European manufacturers to send goods to Russia. Webster would be better off looking at the Near East rather than Central Asia for European supply chains to Russia and pointing fingers at Bishkek.

However, there another issue, that Webster, and Western politicians in general conveniently ignore when talking about sanctions. And that is the impact upon their own economies. Webster states that “Many Western firms with operations in China are notionally exporting to Kyrgyzstan, but with the understanding that these goods will ultimately arrive in Russia. The status quo allows them to trade with Russia with a fig leaf of deniability. By placing Russia-like sanctions on Kyrgyzstan, Washington and Brussels can significantly disrupt China-to-Russia trade via the indirect route.”

Assuming that the EU did remove the ‘fig-leaf of deniability’ and place bans on its own corporations supplying goods to Russia via third countries, there would be immediate negative repercussions. Russia is still a lucrative, medium sized consumer market – its economy is also growing. Cutting off all European-owned manufacturing destined for Russian markets would have significant downstream economic effects.

Productivity & Profitability

Production would decrease, as would profits, as less goods would be manufactured.

Stock Market Declines, Shareholder Unrest

Declining corporate profits would negatively impact stock market valuations, shareholders – some of which are sovereign funds – would be unhappy with reduced dividends.

Unemployment

Workers would have to be laid off, inevitably creating social political dissatisfaction.

Drop In Fiscal Income, Increasing Social Welfare Burden

With lower corporate profitability, government fiscal income from taxes would decrease, while at the same time, an increase in social welfare spending would occur as a result of increased unemployment.

These negative scenarios would all create problems for incumbent governments, with their political popularity decreasing – an effect we are already seeing across Europe. We wrote to Joe Webster outlining these scenarios, as he hadn’t made these observations himself. Instead he has called purely for the cessation of EU owned, third party county, exports to Russia and for sanctions to be placed on Bishkek. He replied, calling us ‘trolls’ and ‘uninformed’. Readers can make up their own minds about the credibility of Western analysts possessing such attitudes when discussing the impact of sanctions.

Webster, and analysts like him pursue an academic style that allows no attempt at any debate, only offering immediate rebuttal. It indicates that Western analysts believe they are always correct and any other perspective is completely, wrong. Regrettably for the likes of Webster, such opinions are neither scientific, nor well researched. This may have future implications.

Summary

The West, and especially the European Union has got itself caught in knots over its imposition of sanctions. Joe Webster is a typical example of an analyst whose actual analysis goes little further than a belief that sanctions cure all trade ills – but does not think through the consequences. He is far from alone, yet as we have explained, the economic and social reality is rather more complex.

Unless a change in these attitudes begins to arise, change will be forced upon these political views. It is a process that may already be underway. The current crop of political thinking has been one-sided, and remarkably basic, with an overarching view that politics takes precedence over trade. The Achilles heel in this position is that democratic governments rely on businesses to conduct trade in order to levy taxes and then uses that money to support their societies. In Europe, it seems that governments are already running out of money and have spent what should have been income for their own citizens on Ukraine. Would further preventing their own businesses from conducting exports to Russia, even via third parties, be the only thing to do at this juncture? Is it completely wise to be beating up countries such as Kyrgyzstan on suspicion of acting as a go-between China and Russia?

Clearly, more thought needs to be put into resolving these issues. The ‘sanctions as a cure-all’ opinion is becoming increasingly shrill, and increasingly misrepresented. Even more suspect is the fact that no Western government asked their tax-paying voters if it was prudent to act in such a manner. The democratic voice as concerns any debate as to spending hundreds of billions of dollars of tax-payers money by both the United States and European politicians has not been referred to.

If more thought is not given by the West in resolving its difficulties with Russia, over time, the types of views expressed by the likes of Joe Webster will eventually become redundant. The harsh reality is that political views cannot be indefinitely extended without fiscal income, regardless of what todays politicians and analysts suggest. Careers are likely to be short-lived. Without political conflict with Russia, many political and pseudo-analytical careers will be over.

Русский

Русский